As Brazil’s largest leftist party gathers to plan the future, a figure that has dominated its past looms ever larger.

Former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva is the unquestioned star of the party conference starting Friday in Sao Paulo, and many still think he could be the party’s standard-bearer once again in 2022 — when he’ll be a 77-year-old cancer survivor who is now barred from seeking office due to a corruption conviction.

Da Silva, who governed Brazil between 2003 and 2010 is fresh out of jail after 19 months behind bars — at least pending a court ruling on appeals of a conviction that followers are convinced was unfair, and pending possible convictions on other charges.

Most analysts see him more as a potential king-maker and strategist for a party he was instrumental in transforming. The former union leader took a party long seen as a radical fringe and brought it to power in 2003, winning adulation from millions for presiding over more than a decade of prosperity and reducing poverty with policies that were far more business friendly than many foes had feared.

That record was increasingly stained by corruption scandals that finally snared da Silva himself, and the 80% approval ratings he enjoyed on leaving office in 2010 have slipped to about 40% today — even so, better than that of the current president.

Still, many on the left still see him as the only politician who can today organize the opposition to far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, who last year ended the Workers’ Party string of victory in four consecutive elections — and who topped a less-charismatic candidate chosen by da Silva.

The left came out weakened from the last election, and President Bolsonaro, a former army captain who much like U.S. President Donald Trump has broken free from conventional ways of governing.

The Workers’ Party remains the biggest party in the lower house, with 54 seats. But even under da Silva, it required alliances with smaller parties to govern — parties that eventually proved unreliable allies.

Da Silva’s Workers’ Party successor, Dilma Rousseff was impeached in 2016 when former coalition members turned against her. And the Workers’ Party candidate in the last election, Fernando Haddad, lost with less than 45 percent of the vote.

Political analyst Fábio Kerche, at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro state, said da Silva has already sent signals that he would try to reach beyond the party core, to the center and center right, possibly building a broader democratic front against Bolsonaro.

He noted that da Silva has shown the ability to attract a broad range of voters and political allies alike, and said, “Once again, this will be his mission.”

During his two mandates, da Silva managed to implement a program heavily focused on fighting extreme poverty, without radicalizing his administration or alienating the business sector, Kerche said.

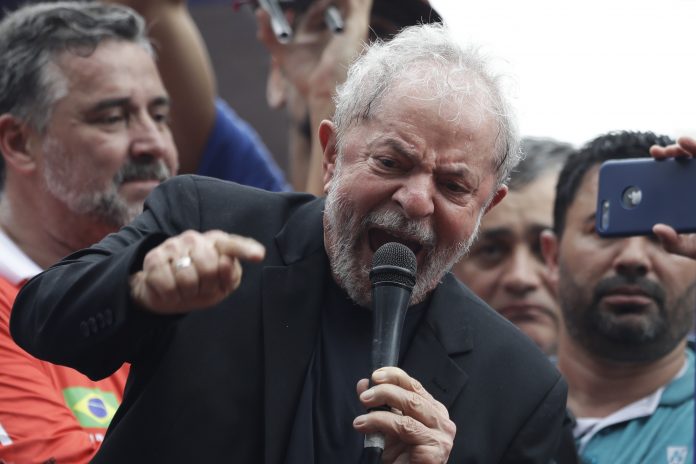

Following his release from prison earlier this month, da Silva gathered thousands of supporters outside the Sao Paulo union that he once led and that later served as the base for his political career.

He was accompanied by former presidential candidate Fernando Haddad and federal lawmaker Marcelo Freixo of the left-wing Socialism and Liberty Party.

But many also wonder how much control the former leader is willing to let go. Da Silva is hoping that the Supreme Court will deliver a ruling that could cancel the cases in which he is accused of corruption and money laundering — and such a ruling would legally open the path to another presidential run.

Brazilian political analyst Carlos Melos said the Workers’ Party has failed to prepare a successor. “There is this structural problem in the (Workers’ Party), which has not consolidated new leaderships in a dimension close to that of Lula.”

Both Rousseff and Haddad lacked the charismatic spark that helped da Silva electrify audiences.

Brazil, like much of Latin America, has struggled to shake off a certain cult of personality. “Unfortunately, right or left, personalities have a greater appeal than institutions,” Melos said.

Whether the former leader runs or not, all agree that he will act as the left’s great strategist, the brain of the campaign.

“Any candidate on the left will have to reach out to the center, or he won’t win,” Melo said. “And any candidate on the left, will have to pass by (da Silva).”q