By SCOTT SMITH

Associated Press

CARACAS, Venezuela (AP) — Reaching for the faucet felt like a frustrating game of chance for Elizabeth Robles. At first, water flowed only one or two days a week, so Robles, president of her homeowners’ association, hired trucks to fill the building’s underground storage tank. With self-imposed rationing, the residents had water — but only for an hour, three times each day. “When you get home at five in the afternoon all sweaty, you couldn’t take a shower,” said Robles, a small business owner and lawyer. “It’s like punishment by water.”

Finally they were fed up. Since the government couldn’t provide water, they decided to drill their own well alongside their apartment building in the tony Campo Alegre neighborhood, an increasingly popular solution among the well-to-do as Venezuela’s water system crumbles along with its socialist-run economy. Venezuela’s meltdown has been accelerating under President Nicolas Maduro’s rule, prompting masses of people to abandon the nation in frustration at shortages of food and medicine, street violence, rampant blackouts — and now sputtering faucets.

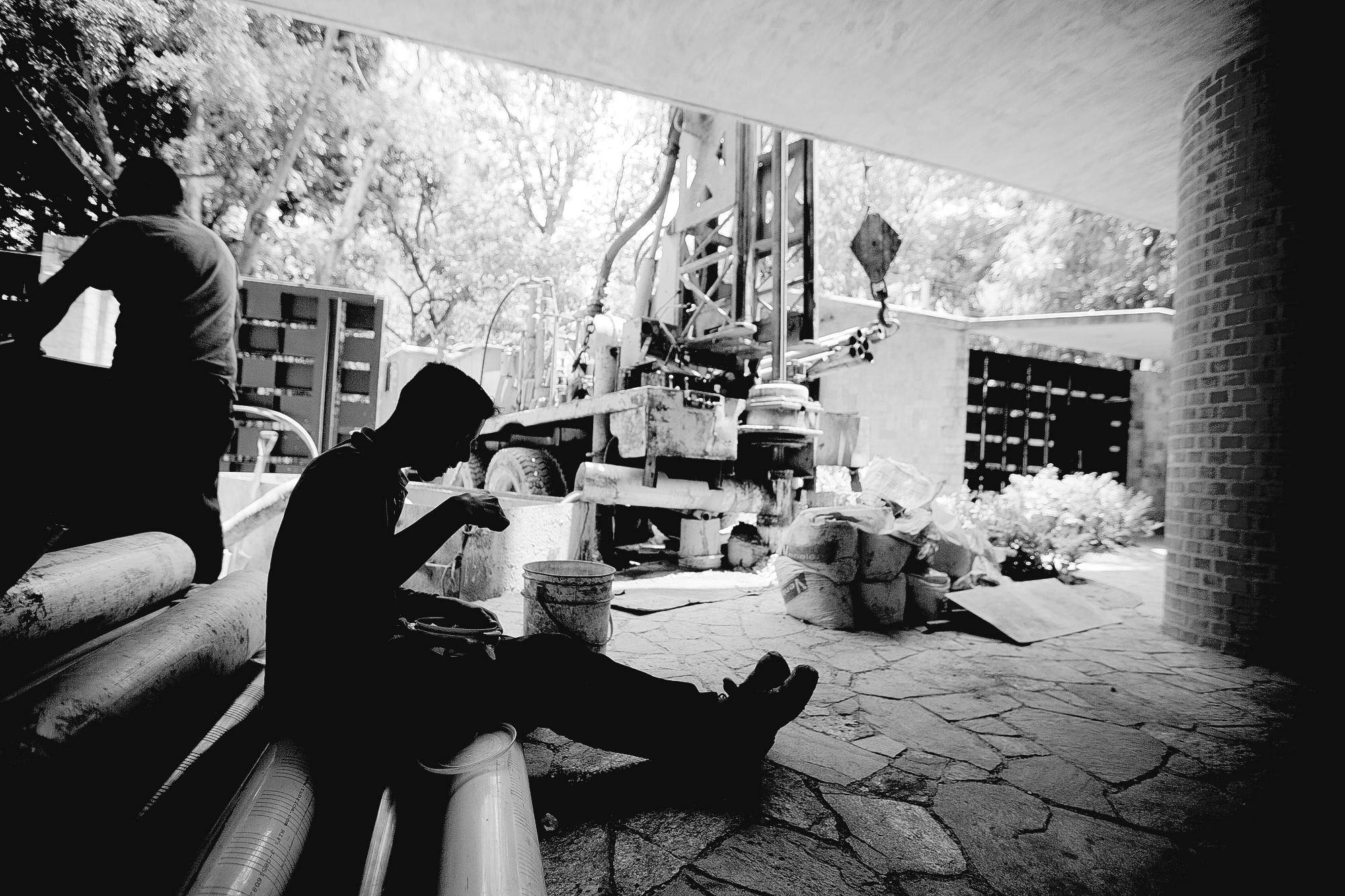

Robles said she and her neighbors hired a drilling firm in February for $7,000 — roughly $280 per family. At least three other buildings on their tree-lined street, which is near the city’s most-exclusive country club, have hired the same engineer. The firm moves its crew and towering yellow rig from one work site to the next. The noisy diesel-powered machine clatters around the clock for several days until the drill strikes water, generally about 260 feet (80 meters) down.

Meanwhile, the less fortunate struggle with dwindling public water supplies, hoping sporadic flows will fill their 150-gallon (560-liter) plastic storage tanks fitted with buzzing electric pumps. Or they stand in line at trickling hillside springs to fill up empty jugs for free.

“Sometimes your dirty clothes pile up,” said Carlos Garcia, an unemployed construction worker who used up eight hours one day filling containers at a spring. Neighborhood water shortages have sparked more than 400 protests countrywide in the first five months of the year, according to the Venezuelan Observatory of Social Conflict.

Caracas once had a world-class water system, pumping water from far-off reservoirs over towering mountains into the valley that cradles the city. Now its pipes are bursting, pumps are failing and a small herd of cattle grazes at the bottom of the Mariposa reservoir outside the city, feeding on grass that should be deep underwater. A lack of rain compounds the lack of maintenance, experts say. Jose Maria de Viana, former president of Caracas’ state-run water provider, Hidrocapital, blames incompetence, and dismisses the government’s explanation that the rainy season has been slow to kick off and replenish drained reservoirs.

The system was designed to see the city through dry spells, he said. “Without staying on top of the problems every day, we’ll have less and less water in the city,” De Viana said. “We’ll only have more protesting and rage.” Officials at Hidrocapital and Venezuela’s Ecosocialism and Water Ministry did not respond to requests for comment by The Associated Press.

Well driller Fernando Gomez at the firm Venezuela Pump Engineering said calls have spiked in the last two months from people desperate for water. The phone rings four or five times a day, compared to one or two calls a week a year ago. He said the company’s single drilling rig doesn’t get a rest.

“Everybody in the world wants it now,” Gomez said. Even the U.S. Embassy has drilled its own well in case the city supply fails. Most of the private wells are going in illegally. The law requires a permit before drilling starts, but the paperwork can take up to two years, and few are willing to wait. When officials stick their nose in, a building’s residents ask the best-connected among them to pull strings. But drilling isn’t an option for the vast majority of Venezuelans who have seen wages pulverized by a collapsing currency and five-digit inflation. The minimum wage amounts to less than $2 a month.

Down a maze of narrow passageways in Petare, one of Venezuela’s most sprawling slums, Carmen Rivero said water is a source of celebration when it flows, and anger when it doesn’t — which is most of the time. She said the neighborhood recently went three months without tap water, and before that, a full eight months. Residents get by filling water barrels from a spring and service from city water trucks. One night recently, a surprise surge of water made her neighborhood break out in joy. “Everybody shouted, ‘Ay, the water came!'” said Rivero, who rushed to a spigot in her home.

She filled up blue tub, like an oversized children’s swimming pool, which hogs the corner of her small concrete and red-brick shack. Frustration over water recently erupted, driving residents into Petare’s streets in protest, some mothers carrying their children. Rivero said heavily armed national guard soldiers wearing riot gear met them, threatening arrest if they didn’t return home. “You’re a human being, and you know we can’t do anything without water,” Rivero recalled telling a soldier. He replied that his family was just like hers, but he had to follow orders.