The quest is on for a better way to kill beautiful but brutally destructive lionfish than shooting them one by one with spearguns.

The voracious invaders with huge appetites, flashy stripes and a mane of venomous spines are a problem in the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico and the East Coast almost to Virginia. They’ve also recently infested parts of the Mediterranean and Aegean seas. With few natural predators, they eat native fish and compete for food.

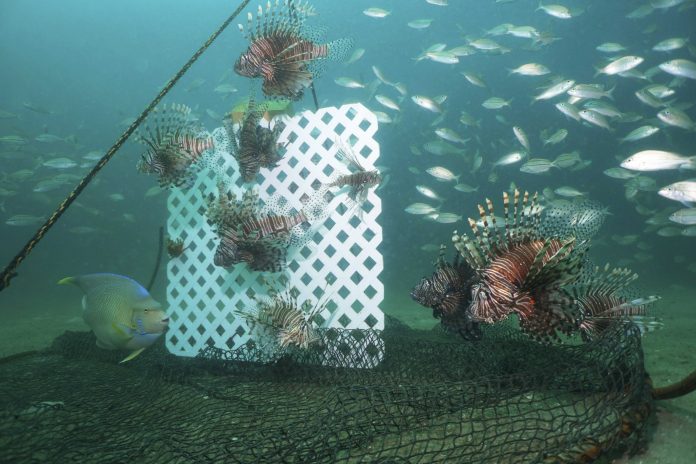

Scientists are looking at two kinds of traps as a way to control the fish outside their native South Pacific and Indian oceans. One is a lobster trap with an entry too skinny for legal lobsters. The other is wildly different, using a vertical sheet of lattice as a lure.

“We don’t think we’ll ever eliminate them but if we can get them under control maybe we can get our ecosystem back,” said Thomas R. Matthews, research administrator for Florida’s Fish and Wildlife Research Institute.

One Florida fisher is setting out the modified lobster traps, and scientists with the institute hope to recruit up to five more.

There also are plans to get lobster fishers to try out and refine the traps with lattice popups invented by Steven Gittings of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Even more than other fish, lionfish like to hang out near anything sticking up from the bottom, and a study Wednesday in the journal PLOS ONE found that those traps caught about 10 lionfish for every unwanted fish.

The study “provides much needed evidence on the effectiveness of a lionfish-specific trap,” said Christina Hunt, a University of Oxford doctoral student who was not part of the study and has published a paper on the sorts of terrain favored by lionfish.

The small amount of unwanted “bycatch” should help win approval if people try to create what would be one of a handful of U.S. trap fisheries, said author Holden Harris of the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agriculture Sciences.

Results with the popup trap compare favorably to the best current commercial fishery cited in the most recent federal bycatch report — a longline fishery that logged 1.8 million pounds (816,500 kilograms) of bycatch to 9.7 million pounds (4.4 million kilograms) of target species.

Gittings, science director for NOAA’s National Marine Sanctuary Program, said he got the idea years ago after watching video about lionfish and lobster traps. “I noticed there were some lionfish inside the traps but a lot more outside the traps, hovering around,” he said.

Using plastic lattice and rebar frames, Gittings fashioned traps that resemble giant change purses when closed. The nets are designed to open when they hit the bottom and lie flat until they’re pulled up, so the only fish caught are those that happen to be around the pop-up.

The hope is that traps could both provide a steady catch for restaurants and reduce lionfish numbers in water that’s too deep for spearfishers, who currently are the only control on the invaders, selling them to restaurants and, in Florida, to Whole Foods Market.

“A regular supply would be nice,” said Tim Lensch, chef at Georgia Sea Grill on St. Simons Island, who said it’s been a couple of years since he’s been able to get any. “We started offering it because it was different and servers could give a cool story — an invasive fish that’s really good to eat.”

Whole Foods, which offers whole lionfish for $10.99 a pound (0.45 kilograms), has been able to get them sporadically over the past couple of years, said David Ventura, the company’s seafood coordinator for Florida. He said traps designed to limit bycatch have potential for an environmentally sound and reliable harvest.

A study at reefs where lionfish had been extensively spearfished off Honduras found that there tended to be more bigger and more fertile lionfish at depths divers couldn’t reach.

Harris’ study “shows that the traps work in shallower waters to catch lionfish. A key next step would be to test these in deeper water,” said World Wildlife Fund marine specialist Dominic Andradi-Brown, one of the outside experts who reviewed the article for PLOS One.

Deeper-water trap tests have already begun.

A comparison of popup traps, unmodified wooden lobster traps and wire seabass traps off of Florida found that the purse traps were by far the best at limiting bycatch, University of Florida marine fisheries ecology professor Will Patterson wrote in a report to Florida’s Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

Researchers also found that none of the traps took very many lionfish, raising questions about whether there are enough at deeper levels in the northern Gulf to make money trapping them there.

The traps also would require new equipment to put them in place, making them less attractive for lobster fishers, said Matthews, the Florida Fish and Wildlife research administrator. “There’s going to be a big learning curve to learn how to deploy it,” he said.

Alli Candelmo, conservation science manager for the Reef Environmental Education Foundation, recently got a $300,000 NOAA grant for a two-year study enlisting lobster fishers to help improve and test the traps.

One question, Candelmo said, is, “How does it need to be weighted to be sure it hits the bottom properly and doesn’t go sideways as it goes down?”

Without a proper landing, the trap doesn’t open. That happened nearly one-third of the time in Harris’ study.