Health care memo to Democrats: There’s more than one way to get to coverage for all.

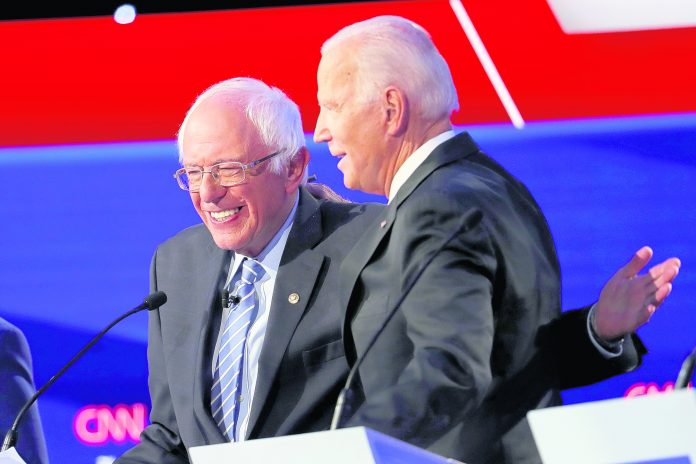

A study out Wednesday finds that an approach similar to the plan from former Vice President Joe Bide n can deliver about the same level of coverage as the government-run “Medicare for All” plan from presidential rival Bernie Sanders.

The study from the Commonwealth Fund and the Urban Institute think tanks concludes that the U.S. can achieve a goal that has eluded Democrats since Harry Truman by building on former President Barack Obama’s health care law.

Health care has sparked sharp exchanges in the Democratic presidential debates, and Tuesday night was no exception. Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren was challenged for being unwilling to say whether her support for Medicare for All would translate to higher taxes for the middle class. Warren said “costs” would be lower, but Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota suggested that was a dodge.

“I’m sorry, Elizabeth,” said Klobuchar. “I think we owe it to the American people to tell them where we’re going to send the invoice.” She urged Democrats not to “trash Obamacare” but build on it.

The study suggests such heated discussions may have more to do with differences over the scope and reach of government than with the ultimate objective of providing universal coverage.

“A goal that they all share — universal coverage — can be reached in different ways,” said Sara Collins, the Commonwealth Fund’s vice president for coverage and access.

The researchers modeled a range of health care overhaul scenarios from tweaks to Obama’s law to a full government-run single-payer plan like Sanders is proposing. Collins said the options studied are not carbon copies of the candidates’ proposals, partly because many details are still in flux. However, they are generally similar.

The study found that a full government-run plan like Sanders’ would cover all U.S. residents, including people in the country without legal authorization. That adds up to more than 30 million currently uninsured people.

However, it would increase U.S. health care spending because of generous benefits with no copays and deductibles. Expanded benefits would include home and community-based long-term care services. Assuming the plan was fully effective in 2020, total U.S. health spending would grow by nearly $720 billion.

The federal government, which would take on costs now paid by employers and individuals, would have to raise nearly $2.7 trillion more in revenue in 2020. Such amounts would require a mix of broad-based taxes, the researchers said, although the report steered clear of how the plans would be financed.

“It is a big lift to get this kind of money, for sure,” said John Holahan, a top Urban Institute health policy expert.

A Kaiser Family Foundation poll out this week found slippage in public support for Medicare for All. Fifty-one percent support such a government-run approach, down 5 percentage points since April. Opposition has risen significantly, from 38% in April to 47% in the latest survey.

The Commonwealth Fund-Urban Institute study also modeled options resembling the plan that Biden is pushing.

It starts with more generous subsidies for “Obamacare” plans and Medicaid expansion in states that have so far refused it. Then it adds a “public option” plan based on Medicare. People with employer coverage would be able to pick the public plan. There would be a mechanism to sign up all those eligible for coverage.

Such an approach would reduce the number of uninsured by about 80%, the study estimated. That would still leave nearly 7 million U.S. residents without coverage, mainly people who don’t have legal permission to be in the country. Under Biden’s plan taxpayer subsidies would only be available to U.S. citizens and legal residents.

Employer coverage would decline by about 10% as some low-income workers switch to the public option.

Assuming the plan was fully effective in 2020, total U.S. health care spending would decline by about $20 billion, a relatively small amount considering the nation’s tab is now more than $3.5 trillion a year. The decline would be partly due to the public option paying hospitals and doctors less than what private plans do now.

The federal government would have to raise from $108 billion to $147 billion more in 2020 to cover the additional cost of expanding subsidized coverage options, a fraction of the cost of Medicare for All.

South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg’s plan overlaps in many details with Biden’s.

The two think tanks are nonpartisan research organizations that have long supported expanded coverage. Their health care work is particularly influential with policymakers on the political left.