By JESSE BEDAYN

Associated Press/Report for America

DENVER (AP) — In a Colorado mountain town, Christine Collins injected herself with black tar heroin while hanging out with friends in her cozy basement a few days after her 30th birthday. Sitting beneath a Happy Birthday sign with hearts scrawled in colorful sharpies, she overdosed.

She awoke to the screams of her friends who fumbled to administer doses of naloxone, which reversed the overdose and pulled Collins back from near death. She has seen dozens of friends wake up from overdoses, and known dozens more that never did.

Such scenes of terror have increasingly played out from Denver’s snow-filled streets to rural towns in West Virginia, with drug overdoses killing over an estimated 100,000 people in 2021, according federal health official’s latest data. That’s roughly one overdose death every five minutes.

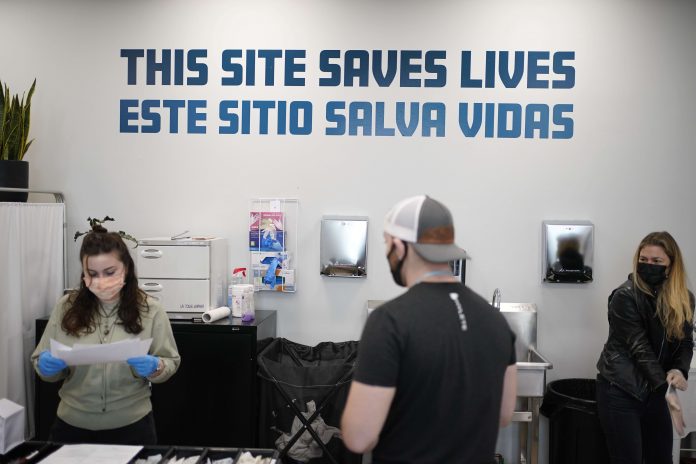

The snowballing death toll has pushed lawmakers in Colorado, New Mexico and Nevada to consider joining New York and Rhode Island in allowing what are often called “safe injection sites.” Also called “overdose prevention centers,” these are places where people can use drugs under the supervision of trained staff who could reverse an overdose if necessary.

Lawmakers in Colorado’s Democrat-controlled Legislature are set to discuss the controversial proposal Wednesday as the measure faces steep odds amid broad backlash from police, Republicans, and lingering questions about whether the sites are even legal in the United States.

The idea of sanctioning the use of drugs including heroin and methamphetamine on these sites — an about-face from the long-waged war on drugs — has garnered stiff pushback.

“You’re basically sending a message that, ‘Hey, it’s okay to do this,’ which has a negative impact on the users’ health, it encourages the drug dealer, and then it still provides that danger to the rest of the community,” said Colorado Rep. Gabe Evans, a Republican and former police officer.

But proponents argue it’s an imperative first step to tackling drug use, with many repeating a one-argument refrain.

“You can’t enter treatment if you are dead,” said Dr. Joshua Barocas, an associate professor at the University of Colorado who studies substance use disorder. “All the data suggests that people are going to do drugs regardless… All we are trying to do is reverse the harm that could come from what people are already doing.”

The trend is growing internationally with centers in Canada, Australia and Europe, but in the U.S. questions remain over whether the Department of Justice will permit such programs amid pushback that the sites merely enable illegal drug use and attract the ancillary crime.

Last year, the Justice Department told The Associated Press it was “evaluating” such facilities and talking to regulators about “appropriate guardrails.” The department did not immediately respond to requests for updated information from the AP this week.Being open to evaluating the sites marks a shift from the Justice Department’s posture under former President Donald Trump, when the department fought against such a proposal in Pennsylvania, arguing that such facilities violate a 1980s-era law which bans operating a place for taking illegal drugs.

Data from sites both in and outside the U.S. found that they can prevent overdoses, with New York City’s centers stopping more than 150 in their tracks within three months of operating. The centers also typically include equipment, such as sterile syringes, and offer resources for drug users to find treatment.

Existing studies, such as a 2021 report from the Boston-based Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, show that sites are linked to fewer ambulance calls — potentially saving tax payer dollars — and didn’t metastasize various crime rates in neighborhoods of operation.

In Nevada’s Democratic-controlled Legislature a proposal to legalize safe injection sites is on the table but has yet to get a hearing, one year after a similar push failed. In New Mexico, a similar bill faces unknown prospects.

Even while a long list of healthcare organizations have signed on in support of Colorado’s bill — including the Colorado Nurses Association, Colorado Psychiatric Society and Colorado Behavioral Healthcare Council — the legislation faces an uphill battle.

While Democrats in Colorado hold majorities in both chambers, Gov. Jared Polis has vocalized his concern over the proposal. The governor’s spokesperson, Conor Cahill, said in a statement Monday that the governor “would be deeply concerned with any approach that would contribute to more drug use and lawlessness.”

Colorado’s Democratic leadership in the legislature have signaled interested in the proposal, but they’ve stopped short of full-blown support.

Republican Evans thinks the solution should be more resources for mental health support and treatment, combined with a firmer law-enforcement response to dealers. Many who are most in need, said Evans, likely won’t spend the time hopping on the public bus to an overdose prevention center.

State Sen. Kevin Priola, a former Republican who defected to the Democratic Party last year citing concerns over the Jan. 6 Capitol riots, is one of the bill’s sponsors. Priola said he’s felt the power of prescription painkillers first hand, having weaned himself early off the drugs following a ski accident that broke his leg.

“I could’ve been a statistic myself,” said Priola, who added that the opposition to such proposals stems from a deep-seated stigma. “People fear what they don’t understand, and they’ve never walked a mile in some of these folks’ shoes.”

Collins, who is now 33 and clean from heroin, struggles. “I don’t make friends anymore because I don’t want to see anyone else die,” she said.

She has watched the scourge of fentanyl rip through communities as she moved from Florida to Louisiana and finally Colorado and believes legalizing the centers is the bare minimum to keep people breathing.

“I know they say: ‘Oh, whatever, it just enables junkies,'” she said. “The fact of the matter is that we may be junkies, but we are somebody’s f—cking families.”