By MIKE CORDER

Associated Press

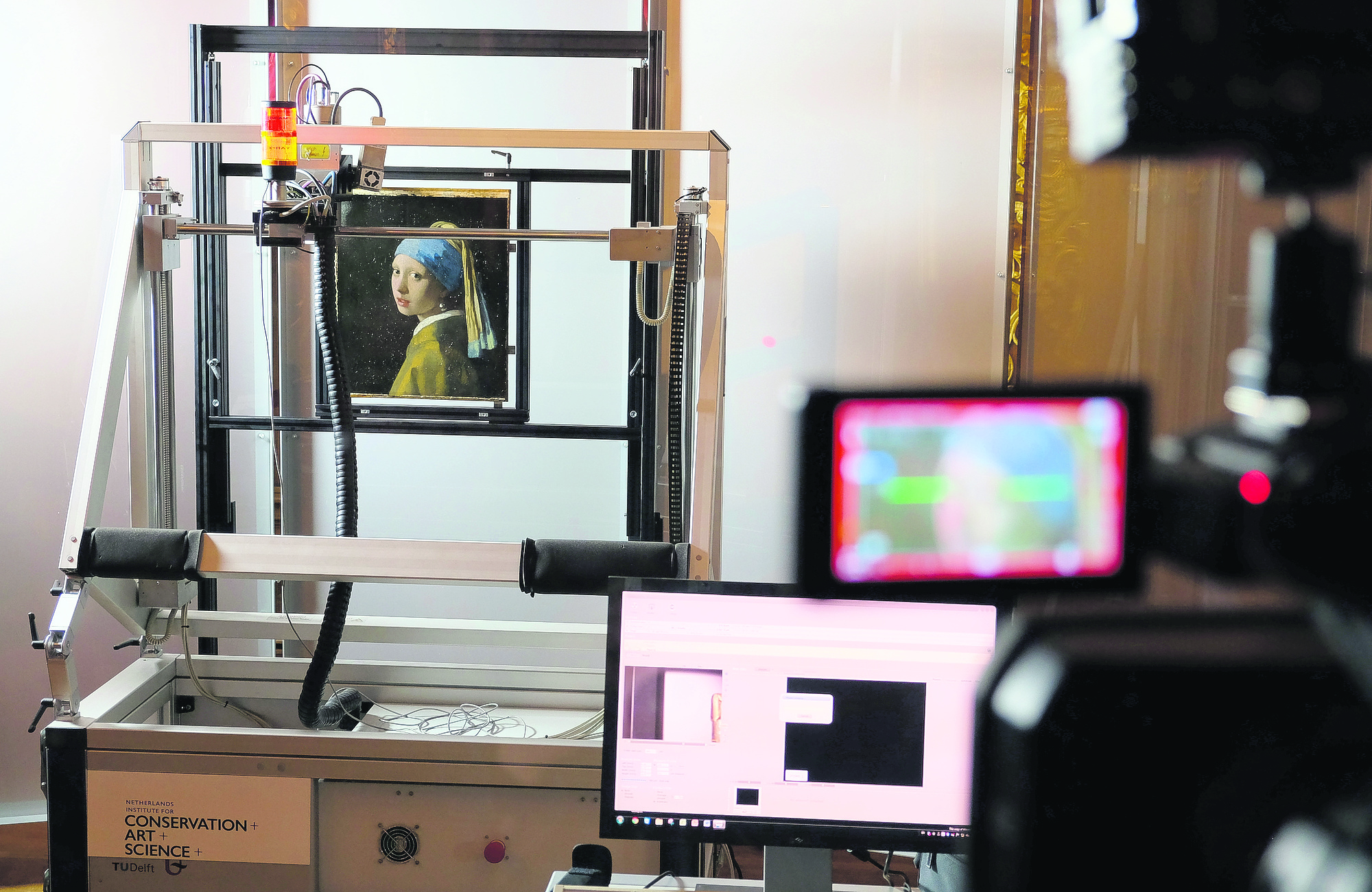

THE HAGUE, Netherlands (AP) — This really is state of the art research. Experts at the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague are using the latest technology to take a long, hard look at one of their most prized paintings, Johannes Vermeer’s “Girl with a Pearl Earring,” and they are inviting the public in to watch.

For two weeks starting Monday, experts are pointing a battery of high-tech machines at the 17th-century masterpiece of a young woman whose enigmatic gaze has earned her the nickname of the Dutch Mona Lisa.

The iconic painting was last studied in 1994 during a conservation project. In those days, they took paint samples from the priceless work to examine.

Since then, technology has made such advances that the museum says scanners and X-ray machines that don’t even touch the surface of the canvas can provide new insights into how Vermeer painted the girl and the materials he used.

The first machine on deck was an X-Ray Fluorescent Spectrometry scanner that uses a thin beam of X-rays to examine the distribution of pigments below the surface of the painting.

“An XRF scan really shows what blobs of paint on the pallet of Vermeer’s studio ended up where exactly and in what intensity on this painting,” said Prof. Joris Dik of the Delft University of Technology that developed the scanner. “So it’s a way of let’s say looking over the shoulders of Vermeer and watching him paint the painting and see him make choices.”

Museum Director Emilie Gordenker said that data collected in the coming two weeks will provide answers to many questions she has about “the girl.”

“How did Vermeer actually build up the surface of the painting? Where did he start? What’s underneath that paint layer?” she said. “What kind of paints did he use? Where did they come from?”

Perhaps most intriguingly of all, the information gleaned by researchers working behind a specially built transparent wall could be used to establish just what the painting looked like when Vermeer applied his finishing touches in around 1665.

“You can imagine a really fabulous digital reproduction,” Gordenker said. “Our best guess of what she originally looked like.”

Meantime, the museum director is looking forward to getting new insights into the famous painting as it undergoes what amounts to a full body scan.

“In every space she looks different and now she looks very vulnerable without her frame,” Gordenker said. “She looks a little smaller. It has a different character and you always learn something from that. The more different angles you can take, whether it’s research or just display, the more you learn about your collection.”

The exhibition in which visitors can watch the researchers in action is called “The Girl in the Spotlight.” It runs through March 11.