By ELLIOT SPAGAT

Associated Press

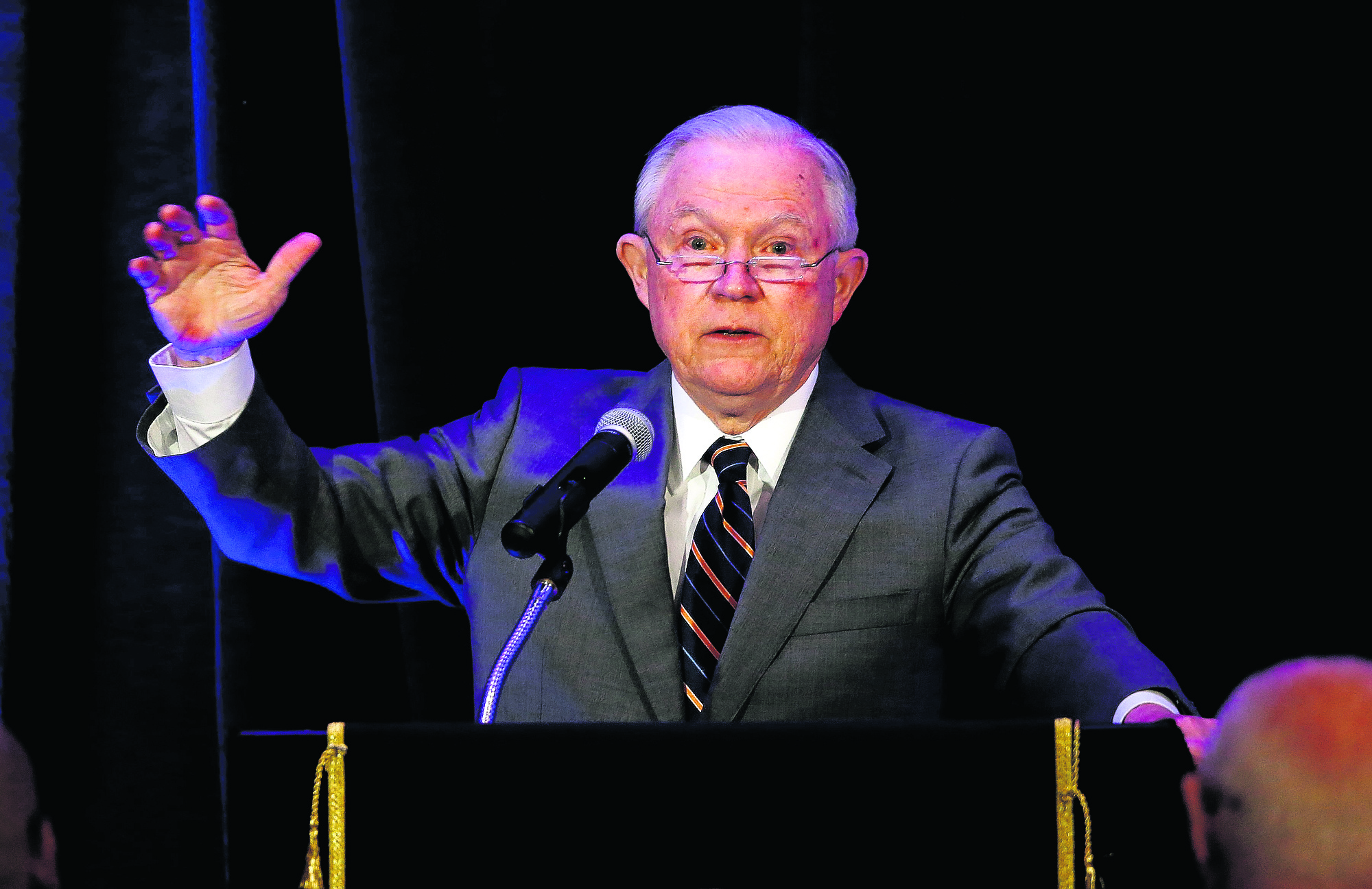

SAN DIEGO (AP) — A “zero-tolerance” policy toward people who enter the United States illegally may cause families to be separated while parents are prosecuted, U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions said Monday. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security said it would refer all arrests for illegal entry to federal prosecutors, throwing its weight behind Sessions’ policy announced last month to vastly expand criminal prosecutions of people with few or no previous offenses. A conviction for illegal entry carries a maximum penalty of six months in custody for first-time crossers, though they usually do far less time, and two years for repeat offenses.

“If you cross the border unlawfully, then we will prosecute you. It’s that simple,” Sessions told reporters on a mesa overlooking the Pacific Ocean, where a border barrier separating San Diego and Tijuana, Mexico juts out into the ocean. Nearly one of every four Border Patrol arrests on the Mexican border from October through April was someone who came in a family, meaning any large increase in prosecutions is likely to cause parents to be separated from their children while they face charges and do time in jail. Children who are separated from their parents would be put under supervision of the U.S. Health and Human Services Department, Sessions said. The department’s Office of Refugee Resettlement releases children traveling alone to family and places them in shelters.

“We don’t want to separate families, but we don’t want families to come to the border illegally and attempt to enter into this country improperly,” Sessions said. “The parents are subject to prosecution while children may not be. So, if we do our duty and prosecute those cases, then children inevitably for a period of time might be in different conditions.” Thomas Homan, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s acting director, said there is no “blanket policy” to separate families as a way to deter others, echoing recent comments by Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen. But he said immigration authorities have long separated families if they have reason to doubt the relationship or if parent is prosecuted.

“Every law enforcement agency in this country separates parents from children when they’re arrested for a crime,” Homan said alongside Sessions. “There is no new policy. This has always been the policy. Now, you will see more prosecutions because of the attorney general’s commitment to zero tolerance.” Advocacy groups blasted the moves as cruel and heartless, especially in cases where the family is seeking asylum in the United States.

“Criminalizing and stigmatizing parents who are only trying to keep their children from harm and give them a safe upbringing will cause untold damage to thousands of traumatized families who have already given up everything to flee terrible circumstances in their home countries,” said Erika Guevara-Rosas, Amnesty International’s Americas director.

U.S. Rep. Bennie Thompson of Mississippi, the top Democrat on the House Homeland Security Committee, said, “Criminalizing parents seeking protection for themselves and their children is inhumane, excessively punitive, and can deliberately interfere with their ability to seek asylum.” The American Civil Liberties Union is challenging the practice in a case involving a Congolese asylum seeker who was separated from her 7-year-old daughter for five months and a Brazilian woman who was separated from her 14-year-old son after being arrested and serving nearly a month in jail for illegal entry. At a hearing in San Diego last week, a Trump administration lawyer did not dispute a report in The New York Times that more than 700 children had been taken from their families since October.

The attorney, Sarah Fabian, said she couldn’t say whether there was a shift since Trump took office because officials didn’t have historical data. A sharp increase in prosecutions will strain the court system. Sessions said he has assigned an additional 35 prosecutors and 18 immigration judges to the border regions.