By MONIKA SCISLOWSKA

and VANESSA GERA

Associated Press

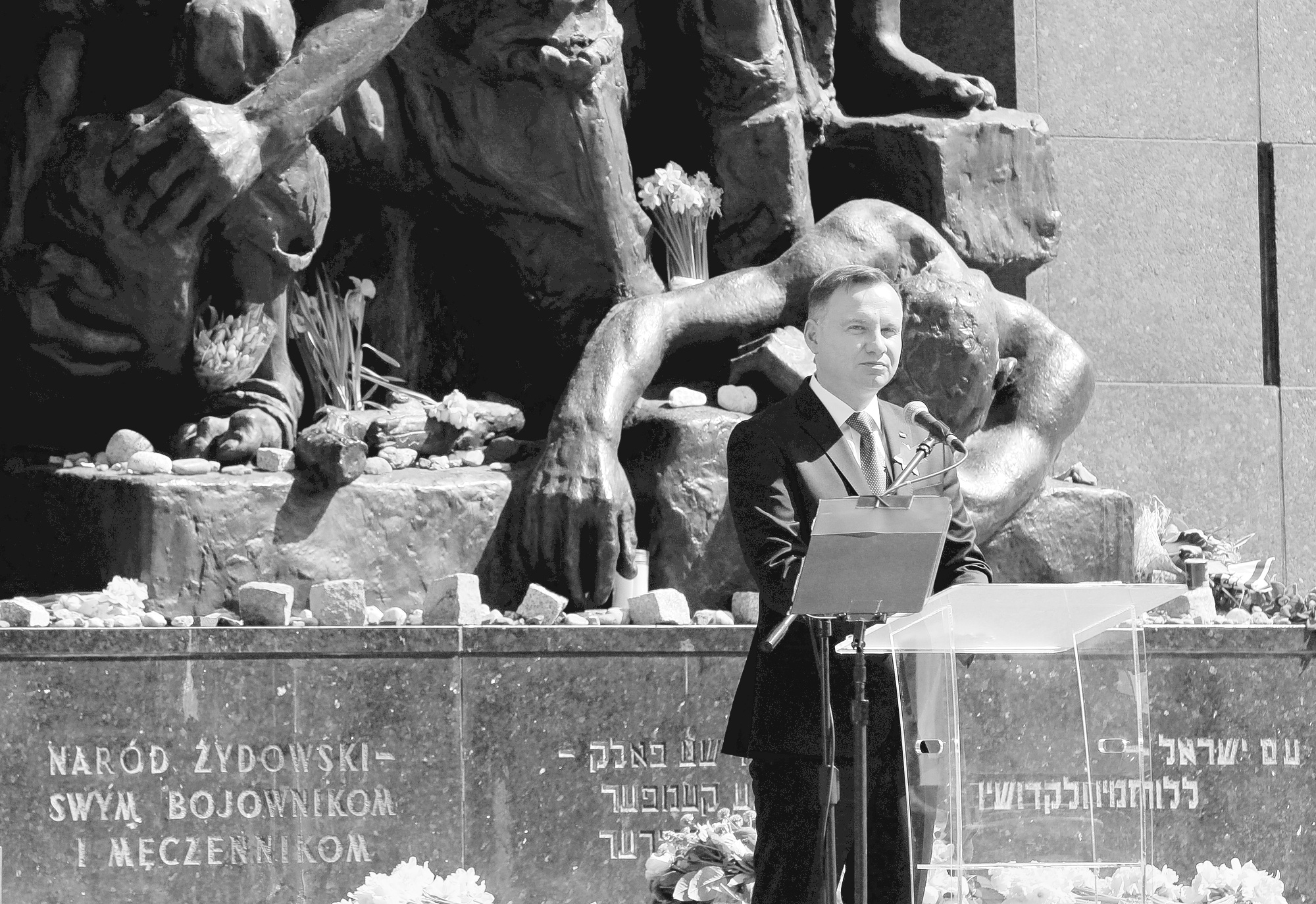

WARSAW, Poland (AP) — Sirens wailed, church bells tolled and yellow paper daffodils of remembrance dotted the crowd as Polish and Jewish leaders extolled the heroism and determination of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising fighters on the 75th anniversary of their ill-fated rebellion. Polish President Andrzej Duda and World Jewish Congress President Ronald Lauder said the hundreds of young Jews who took up arms in Warsaw in 1943 against the overwhelming might of the Nazi German army fought for their dignity but also to liberate Poland from the occupying Germans.

The revolt ended in death for most of the fighters, yet left behind an enduring symbol of resistance. “We bow our heads low to their heroism, their bravery, their determination and courage,” Duda told the hundreds of officials, Holocaust survivors and Warsaw residents who gathered Thursday at the city’s Monument to the Warsaw Ghetto Heroes. “Most of them died … as they fought for dignity, freedom and also for Poland, because they were Polish citizens,” Duda said.

Lauder said although the Nazis were defeated and crushed 73 years ago, “oppression and oppressors have not gone away and we need each other today like never before.” “Jews, Catholics, Poles, Americans. All free people should stand together now to make sure that our children and grandchildren never know the true horrors that took place right here,” he said. People stopped in the street and officials stood at attention as sirens and church bells sounded at noon to mourn the Jews who died in the uprising, as well as the millions of others murdered in the Holocaust.

The daffodil tradition comes from Marek Edelman, the last surviving commander of the uprising, who on every anniversary used to lay the spring flowers at the monument to the fighters. He died in 2009. At a separate ceremony at Warsaw’s Town Hall, three Holocaust survivors — Helena Birenbaum, Krystyna Budnicka and Marian Turski — were given honorary citizenship of the city. Hundreds of people also attended a grassroots commemoration that was, in essence, a boycott of the official state observances. Many people there expressed anger at Poland’s conservative government, which seems to tolerate anti-Semitism despite its official denunciations of anti-Semitism.

“I am not attending the official ceremonies this year because the government is supporting the rise of a dangerous nationalism,” said Tanna Jakubowicz-Mount, a 72-year-old psychotherapist who carried photos of a grandmother and aunt who were executed by the Germans. “We cannot agree to this.” The alternative observances began with Yiddish singing and daffodils placed at the monument to a Jewish envoy in London, Szmul Zygielbojm, who committed suicide after the revolt was crushed to protest the world’s indifference to the Holocaust.

Participants then paid homage to the victims at several memorial sites in the area of the former ghetto, including at Umschlagplatz, the spot where Jews were assembled before being transported to the Treblinka death camp. There, one by one, people spoke Thursday about their family members killed by Hitler’s regime. Signs of rising nationalism in Poland have also strengthened the resolve of those seeking an inclusive society. This year a record 2,000 volunteers were handing out the paper daffodils, which have become a moving symbol of a mostly Catholic society expressing its sorrow at the loss of a Jewish community that was Europe’s largest before the Holocaust.

There were also scattered private observances, including by American Jews returning to the soil where their parents and grandparents lived and died. Some 40 members of the Workmen’s Circle, a group from New York City that promotes social justice, honored the resistance fighters at the remains of a bunker in 18 Mila Street. The son of an uprising survivor read personal recollections from the diary of his mother, Vladka Meed, while the group’s director, Ann Toback, vowed on what she called “hallowed ground” that the uprising would continue to inspire modern resistance to oppression.

The Warsaw Ghetto uprising broke out April 19, 1943, when about 750 young Jewish fighters armed with just pistols and fuel bottles attacked a much larger and heavily armed German force that was putting an end to the ghetto’s existence. In their last testaments, the fighters said they knew they were doomed but wanted to die at a time and place of their own choosing. They held out nearly a month, longer than some German-invaded countries did. The Germans razed the Warsaw Ghetto and killed most of the fighters, except for a few dozen who managed to escape through sewage canals to the “Aryan” side of the city, Edelman among them.