By MARÍA VERZA

Associated Press

MEXICO CITY (AP) — Analysts in Mexico said Monday that President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s successful push to hold the weekend’s recall vote could, paradoxically, leave Mexico’s democracy weaker.

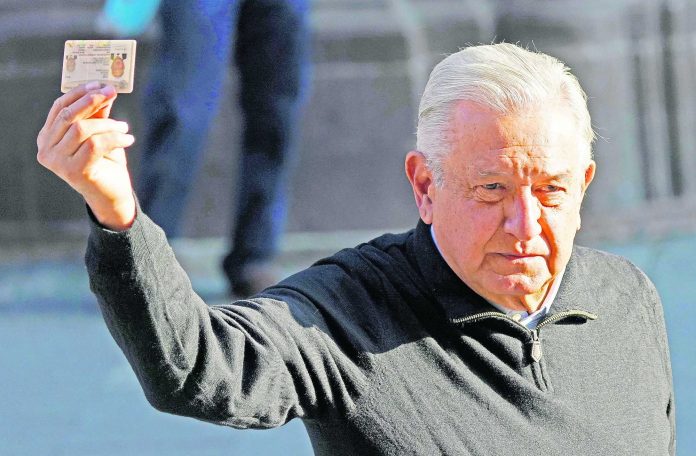

López Obrador declared Sunday’s referendum, in which he was strongly supported by the few Mexicans voters who participated, as “a complete success” and “a historic event.”

He described the vote as a victory for “participative democracy,” noting Mexicans had never before been allowed to vote on whether a president should be recalled from office.

But his Morena party used illegal, old-style electioneering tactics to get out the vote for what was a largely symbolic vote.

López Obrador was never in doubt of losing the referendum Sunday, with his approval ratings currently hovering around 60%. Near-final vote tallies Monday showed that about 92% of the ballots cast said he should remain in office.

Still, the president saw getting large numbers of voters to turn out was the real measure of his political movement. Turnout was about 16.5 million, or only about 18% of eligible voters — far below the 40% turnout needed to make the vote binding.

The leader of López Obrador’s party, Mario Delgado, boasted about driving around in a van, picking up people to take them to polling places, a practice that is illegal in Mexico.

Delgado posted photos in his social media accounts showing him driving a van painted with the words “Do you want to vote? I’ll take you there!” The van was later shown loaded with people who had voted.

Clara Jusidman, an economist and civic activist, said some government employees also were required to bring a minimum number of people to polling places. That is a practice reminiscent of the old Institutional Revolutionary Party, which governed Mexico for seven decades without interruption until it lost the 2000 elections.

“A lot of rules were broken that had been established to protect against government intervention, the use of public funds to promote (a vote) and ‘client’ politics,” Jusidman said, referring to people who feel they have to vote to preserve their government benefits.

And the president himself has criticized elements of the electoral system that emerged after decades of near one-party rule in an effort to strengthen democracy, among them independent electoral authorities established in the late 1990s to ensure fair play and equity in elections.

López Obrador has pledged to overhaul the National Electoral Institute, contending that it is too expensive and is hostile to his Morena party.

Critics said Sunday’s vote was the real waste of money. They said it cost almost $80 million and was just a way for López Obrador to rally his base midway through the single term allowed Mexico’s presidents. They worry that changes to the electoral institute are likely to decrease its autonomy and independence.

In fact, López Obrador has expressed dislike for independent regulatory and oversight bodies in general, such as in government transparency and information access. He has sought to eliminate some of them.

Luis Miguel Pérez Juárez, an expert in democratic transitions at the Monterrey Technological Institute, said the president has never had much affection for the electoral institute, known by its initials as the INE, which occasionally tries to limit what elected officials can say in the runup to elections.

“Ever since he came to power, the INE has bothered him,” Pérez Juárez said.