As he worked on early drafts of “The Catcher in the Rye,” a novel which proved both scandalous and life-changing, J.D. Salinger considered adding his generation’s idea of a trigger alert.

“I think there’s going to be a lot of swearing and sexy stuff in this book,” warns narrator Holden Caulfield, in a paragraph on page 18 of Salinger’s manuscript, part of an upcoming exhibition at the New York Public Library. “I can’t help it. You’ll probably think I’m a very dirty guy and that I come from a terrible family and all.”

“The trouble is,” Holden adds, “everybody swears all the time. And everybody’s pretty sexy.”

Salinger apparently changed his mind. He drew a large X through the passage and wrote “delete” in the margins. Starting in 1951, when the book was published, millions of readers would discover the truth for themselves.

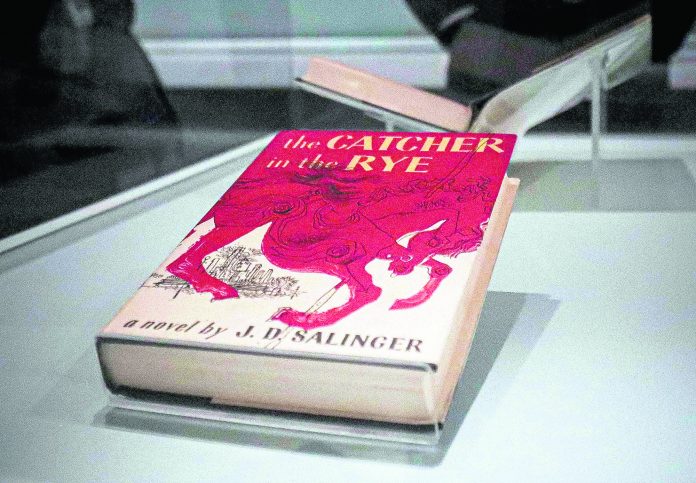

The library exhibit, titled “JD Salinger,” opens Friday and runs through Jan. 19 at the historic 5th Avenue branch in Manhattan. It continues a surprisingly eventful centennial for Salinger, who died in 2010 and avoided publicity for much of his writing life. His literary estate approved new print editions for the first time in decades of the four books he allowed to come out in his lifetime — “The Catcher in the Rye,” ”Franny and Zooey,” ”Nine Stories” and “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction.” And for the first time ever, the literary estate authorized e-book editions.

Salinger’s estate is overseen in part by his son, Matt Salinger, who has also said that readers will, at some point, see the books his father worked on after he stopped publishing in the 1960s. In announcing the exhibit last week, the younger Salinger cited the public’s lasting curiosity.

“When my father’s long-time publisher, Little, Brown and Company, first approached me with plans for his centennial year my immediate reaction was that he would not like the attention,” Matt Salinger wrote. “He was a famously private man who shared his work with millions, but his life and non-published thoughts with less than a handful of people, including me. But I’ve learned that while he may have only fathered two children there are a great, great many readers out there who have their own rather profound relationships with him, through his work, and who have long wanted an opportunity to get to know him better.”

Drawing upon archives made available by Matt Salinger, the exhibit is not the tell-all that some fans might have wanted. There are no unreleased novels or stories, and no images of Salinger’s widow, Colleen Salinger, or of the mother of Salinger’s two children, Claire Douglas. His affair in the early 1970s with author Joyce Maynard, a college student when he befriended her, is not mentioned. But the library does offer an eclectic, revelatory and sometimes quirky range of materials, from a Royal manual typewriter to a bowl Salinger made as a boy to videocassettes of Marx Brothers comedies and other films he liked to watch. A bookcase from his bedroom includes “The Oxford Book of Detective Stories,” a collection of Robert Browning poems and three volumes on “Zen and the Zen Classics,” reflecting his immersion in Eastern religion and philosophy. Letters to his literary representatives document his immersion in the publishing process, from sales and royalties to the cover design of paperbacks.

Declan Kiely, the library’s director of special collections and exhibitions, said that the materials on display demonstrated Salinger’s “meticulousness, possibly bordering on the obsessive,” although “obsessive in a good way.”

“You have to be obsessive to produce a body of work, to be true to your art,” Kelly said. “It (the exhibit) reveals Salinger the man — in terms of simple hobbies, the modesty, the quotidian aspects of his life. There’s nothing fancy or frilly about Salinger.”

Salinger’s career as an author is captured through clippings of his early stories, manuscripts, copies of his books and letters to his publishers. A working draft of “Franny and Zooey” was titled “Ivanoff the Terrible, subtitled, “An Ontological Comic Drama With a Little Morning Music,” and included an opening section which apparently refers to his years as a counter-intelligence officer in Europe during World War II. (Salinger fans had long wondered whether “Ivanoff” was a separate, unreleased book).

“Early in the Normandy campaign, we were issued little olive-drab crystal balls to help pass the time in the foxholes,” Salinger writes, a reference to the D-Day invasion, when he was among those landing on Utah Beach. “Mine came with a rather ominous looking crack in it, but I see a few things, I see a few things …”

The one-room library exhibit tracks Salinger’s life. There are childhood photos and images from his military service, many highlighting his dark eyes, extended jaw and the hint of a Holden-like smirk. Pictures from the 1960s and 1970s with his children, Matt and Margaret, capture Salinger in middle age, in rural Cornish, New Hampshire. A handful of shots show him in old age, holding a grandchild or relaxing on the grounds of his home. After Salinger’s death, an old friend from the military, John L. Keenan, wrote to Matt, telling him about his father’s horrifying experiences, which led to his being hospitalized after the war.

“He was among the first American troops to enter Paris, as well as with the first American to cross the German border at the Siegfried Line. He endured the hardship and perils of the battles of the Bulge and the Ardennes forest,” Keenan’s letter reads. “Though like the rest of us, not happy to be there, he accepted his ‘lot’ and did more than what was expected of him. He was brave under fire and a loyal and dependable partner. On many occasions in the course of an assignment, although pinned down by artillery, machine gun or small arms fire, he did what had to be done.

“I admired him then and I grieve for him now.”q