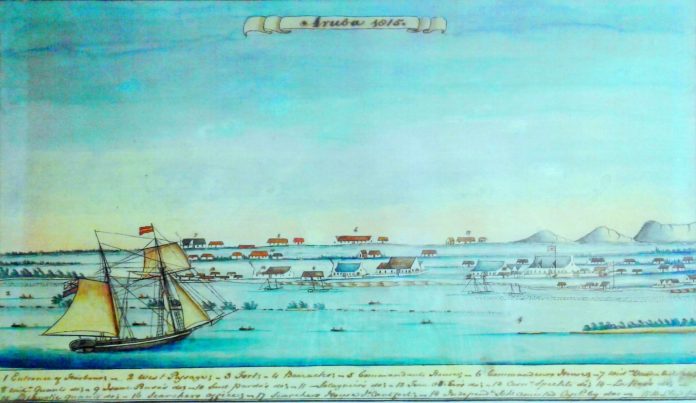

Just over seventeen hundred people lived on Aruba in 1816. Trade with the Gulf of Maracaibo was a transit-trade; shipments were received from Curacao merchants and return-cargoes consisting of dye-wood and goatskins were sent there. Eight merchants and eight shopkeepers reside on our island, as well as 78 sailors. Fishing was only carried on in “canoes”. Of the 319 persons whose calling was known 194 were planters. There must have been a moderate prosperity, since two goldsmiths found occupation here.

An inventory of fort Zoutman makes it very clear that government –property was in a sadly neglected condition, “two benches, two tables, two iron pots, four halivats (an Aruban measure, half vat about 8 gallons), two water-casks, a soldiers’ quarters, 17 workable and defective muskets, and 20 cartridge-pouches. With regards to private houses nothing was reported. The garden of “bakkoval” and Fontein according to old usage served as “special allowance” for the commander. All the soil belonged to the government, but Aruba was not classed as a government plantation like Bonaire. However, those cultivating the little gardens or cunucus did not pay leases. Rates were not levied, but every inhabitant was obliged to work two days a week for the government, a kind of statute labor. It was possible, however, to have oneself replaced by a slave. Tree native could together send one permanent slave.

Pic.2. Oranjestad at the beginning of the twentieth century

Pic.2. Oranjestad at the beginning of the twentieth century

When more people got an opportunity to settle here the feudal laws maintained by the Dutch West India Company until 1791, which had been left intact by the government afterwards, could no longer be kept up. In 1823 the whole of Aruba was still regarded as crown-land. In that year the residents were permitted to obtain the ownership of the land they had received as

Pis. 3 the salt pan at Rancho today a flea market opposite the gasoline station at the harbor

Pis. 3 the salt pan at Rancho today a flea market opposite the gasoline station at the harbor

concessionaries by purchase. The gold –finds of 1824 as well made further provisions necessary. They came in 1829: the colonial administration maintained its rights to the gold, but would give compensation. Under Governor Reinier F.Baron Van Raders the last traces of feudal law on Aruba were obliterated in 1841, and replaced by proprietary rights, a measure receiving renewed official sanction in 1924. Owing to the conditions prevailing under the Company’s sway and their development until the time of Van Raders, the growth of large holdings was impossible on our island. In this Aruba differs from the other islands, a difference emphasized by its social consequences. A man who has a holding of his own also wants his own house.

Pic. 4. Mainstreet Oranjestad in the beginning of last century.

Pic. 4. Mainstreet Oranjestad in the beginning of last century.

During the first fifteen years after Aruba had been handed over to the Dutch again about a thousand new residents settled on the island. Most newcomers were traders establishing themselves “on the Bay”. In the Commander’s Journal of 1st October 1822 we read:

“Since from time to time requests have been handed to us for permission to construct houses on Horses’ Bay in the island of Aruba, it does not seem improbable that after some years a regular village will occupy the above site. And because it is necessary for some order and system to be introduced in placing these houses, so that they shall not be built at random in a disorderly and scattered manner, but shall on the contrary be constructed in rows so as to facilitate the making of streets and roads, in which manner a proper village may be founded, we have deemed fit to make known our above observations to the commander of the island of Aruba by copy of this letter, enjoining him to see to it that our intention is complied with and to take due care that the sites for the building of the houses will be selected after proper deliberation and assigned to those who shall have obtained our permission”. In 1822, therefore, it is already foreseen that “on the Bay”, as the nameless spot was still styled, a regular village will arise. People were coming to live there, and apparently built their houses anyhow all round the water. On 16th February 1927 Commander Simon Plats writes to Governor Paulus R. Cantz’laar that the extension of the village and the difficulty resulting from this for the ward-ad district-masters to fulfil their duties had given rise to a division of the little place into two sections by means of a street running almost due north and south.

Plats next informs Cantz’laar: “In consequence of this division I have, on the strength of art.525 regarding the commander of Aruba, appointed as warden of the east section of De Oranjestad, Corn. Raven, inhabitant of same, and as warden of the west section Pieter Wuurman (name hardly legible), also residing in the part of the town coming under his supervision”. So in February of 1827 the “village” on Horse’s Bay bore the name.

Now during one of many visits to Aruba, of Governor Cantz’laar, when this dignitary proposed a toast to “the prosperity of the Horses Bay” Those at the table observed that the village that came in to being had no name. Cantz’laar had the idea to honor our King Willem I, however this would not do, for there was already a Willemstad, on Curaçao. Then Jacob Thielen I stood up and proposed Oranjestad (Orange city) as a solution. The name Oranjestad came to be on a Tuesday, the third of August 1824. Hardly the name had been heard by those preset when they all broke out into cheers and cries of, “Long live the Oranjestad! May it grow and thrive.

Discover an Aruba which no other could share with you. Discover and explore and take your experience home with you. Our renowned indigenous and educative session has been entertaining curious participants for decades. Mail us at etnianativa03@gmail.com to confirm your participation. Our facilities and activities takes place close to your hotels area.