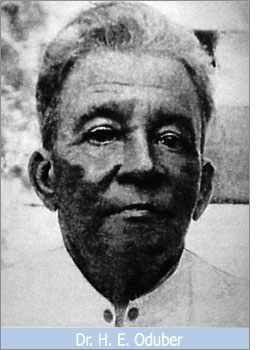

| Aruba has many great doctors nowadays, but just imagine being a doctor back then in the 1800’s how primitive that seems and worst yet, with not even a hospital on the island. Doctor Horacio Eulogio Oduber (1862-1935) was the first Aruban physician. He was so loved and highly respected by the people. He even has a street bearing his name, Dr. Horacio Oduberstraat. It is not a well-known street, because it is rarely used. But it really does exist. You will find it behind the old country laboratory, parallel to the Hospitaalstraat in Oranjestad.

His parents were Francisco Oduber and Johanna Prudencia Eckmeyer, who were both born in Aruba in the year 1827. After his general education, “Acho”, as he was affectionately known, set course at the age of 18 to the University of Maryland in the American city of Baltimore. A few years later he returned as an accomplished physician, the first Aruban to hold this title. Doctor Acho was a highly respected physician, who traveled around the island with a horse and cart (kietrien) to visit the sick. He was known as a sympathetic man with a young heart. Someone who had a personal relationship with his patients and who carried out his profession with great enthusiasm. His patient file consisted of the few thousand inhabitants that Aruba had at the time (eight thousand souls according to an estimate from 1910). They were predominantly farm laborers with little financial means. Often the doctor was paid naturally, either with beans, peanuts or other agricultural crops. His horse was not passed over. Especially for this animal, the households always kept a little bit of hay aside. Doctor Oduber was a doctor at a time that seems almost primitive today. There was no electricity or running water on the island. No phone. No motorized transport. And medical science was also still in its infancy. Many people died of infections. Viruses or childhood diseases had never been heard of. Nor penicillin, blood transfusions or X-rays. The concept of bacteria was well known, but was still far from being understood, let alone that therapy and prevention were aimed at it. All in all, there was not much a doctor could do other than bloodletting and warming limbs. In addition, Dr. Oduber was faced with another problem in Aruba, namely the lack of a hospital. That is why patients sometimes slept with him; free. In his house on the Wilhelminastraat he had set up a few rooms especially for this. Here, incidentally, the doctor also performed all other activities that belong to a hospital, including operations. Amputations, for example. In the absence of opium or any other anesthetic, patients were first fed drunk with rum. In fact, you could say that the doctor’s house at Wilhelminastraat was Aruba’s first hospital. Doctor Acho was married twice. First with Antonia Penso, later with Mariana Betanco. He had four sons and a daughter, namely Francisco (1884), Jacobo (1893), Johanna (1895), Polidor (1899) and Horacio (1905). Two of his sons, Francisco (Fanchi) and Jacobo (Cobito), both became doctors in adulthood. Fanchi married Constanza van der Biest in Venezuela in 1915 and continued to live and work in that country for a long time, because there was not enough work in Aruba at the time. It was not until 1944 that he came to Aruba with his family, when the expansion of the Lago had caused a population increase and there was a demand for more doctors. The second son, Jacobo (Cobito), also chose his father’s profession. And he also had to move to a different environment for work. He married Albertina de Veer and started his career in Curaçao, which island he left when the demand for doctors in Aruba increased. Doctors Cobito and Fanchi both enjoyed good reputations, as did their old man. When Aruba’s first real hospital was constructed in 1976, the Executive Council organized a competition around the naming. Among the 138 entries were suggestions such as Mamona Hospital, Aruba Hospital, Dr. De la Fuente Hospital, Hospital Betico Croes and Hospital General di Aruba. Although the Dr. Horacio Oduberstraat already existed, younger generations were not familiar with the pioneer of Aruban healthcare. By then he had already died for over forty years. Horacio’s family was delighted with the final choice of the Executive Council. For instance, the youngest son, also called Horacio, wrote an English-language letter to committee member Alida (Dachi) Lampe in 1976 and thank every one of them for their thoughtfulness in remembering his father and consistently honor his name. “On my last visit to Aruba I saw the construction of the hospital in process and somehow I had an inner-feeling that my father would have rejoiced the project had he lived to see his beloved Aruba with such a hospital. I remember as a small boy that he used to lodge the operated persons without means in the rooms we had in our yard. Since the committee is composed of young people I wonder who could have brought up the bright idea of remembering my father. Again, thank you all.” Source: Aruba Heritage

|