It was 93 degrees and humid when I set out on a 4-mile stroll through a Louisiana swamp.

Crazy, you say? But let me tell you what I found there, in the Barataria Preserve of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve.

A symphony of frogs. A 700-year-old tree. And a verdant landscape of dripping moss and neon green that seemed to melt with the heat into the woods and wetlands.

Fan-shaped palmettos waved hello along the trails. Strange formations of cypress trees known as knees pushed up through the swampland. Moss cascaded from branches overhead. I half-expected to spot a mythical creature like the rougarou — half-wolf, half-man in Cajun folklore — lurking in the forest. But no werewolves or fairies crossed my path, though I was startled by the creepy sight of a couple of alligators floating motionless and half-submerged in dark waters.

I was also enchanted by the continuous soundscape of creatures baying, chirping and croaking, from bronze frogs that sound like bicycle horns to narrowmouth toads that sound like sheep.

That night, back in my air-conditioned hotel room a half-hour drive from the park in New Orleans, I tweeted out a few seconds of a video I’d taken on my cellphone, showing the wet, green world I’d encountered, along with its natural soundtrack. A short time later, the park’s official Twitter feed, @JeanLafitteNPS, retweeted it with this message: “That’s the way to stand up to a south Louisiana summer — pack a bottle of water & stroll thru the swamp.”

I had to find out who was behind this empowering never-mind-the-weather message, and a couple of phone calls led me to Kristy Wallisch, a park ranger who handles Jean Lafitte’s public information.

“Traditionally summer is our low season because it’s very hot,” Wallisch said. But while locals head to Gulf Coast beaches this time of year to escape the heat and humidity, the park does get out-of-towners — like me. “Kids are out of school, people are traveling, and they’re saying, ‘OK, it’s going to be hot and humid, but we’re also going to see and hear amazing things we’re never going to see and hear anywhere else,'” she said, adding: “You’ll forget the heat and humidity three days later. But you’ll always remember what a wonderful time you had.”

The Barataria Preserve is one of six distinct sites that make up Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve. The other sites include a visitor center in New Orleans’ famous French Quarter and the Chalmette Battlefield, where the Battle of New Orleans was fought in 1815. It was the final great battle of the War of 1812, in which Andrew Jackson led the Americans to a David-versus-Goliath triumph over British forces.

Jackson owed his victory in part to the man for whom the park is named: Jean Lafitte. Lafitte was a privateer — OK, let’s just call him a pirate — who supplied Jackson with soldiers, guns and more. Had Lafitte shown up at the docks in New Orleans with his contraband, he would have had to pay taxes on it. Instead, he used the waterways as back roads. Some of his operations were based where the Barataria Preserve is now.

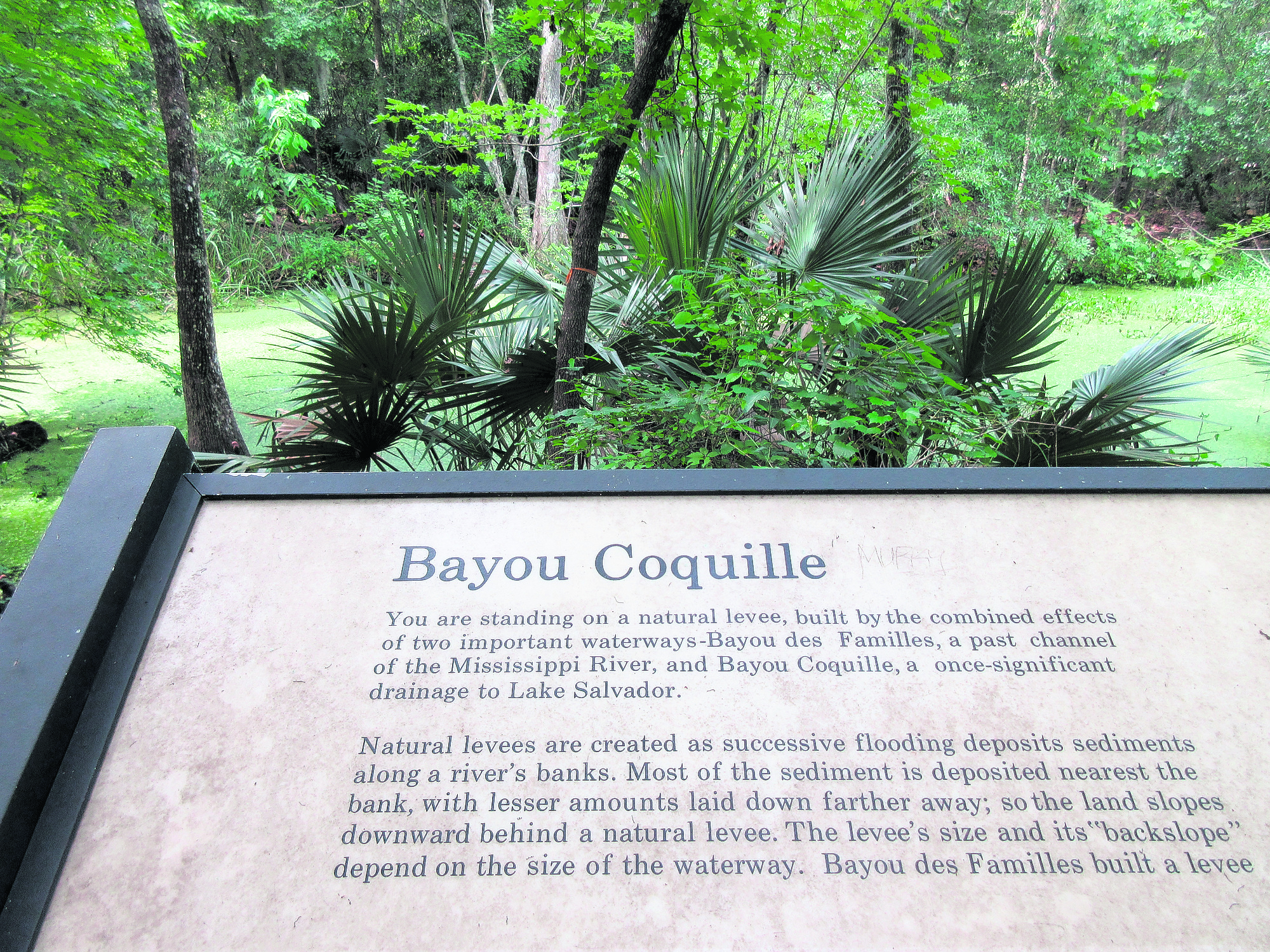

My visit included a walk on the Palmetto Trail and the Bayou Coquille Trail. Coquille is the French word for shell, named for an enormous mound of shells discarded by Native Americans who once inhabited the area. A sign marks that spot today.

Another sign showcases the “Monarch of the Swamp,” a massive old-growth bald cypress tree estimated to be 700 years old. These trees were prized in the South because they were resistant to termites, so many of them were cut down.

“We always wonder why that one survived,” Wallisch said of the Monarch, adding that the joke goes that loggers must have encountered it on a Friday afternoon when they were ready to knock off work and said, “We’re not starting on that tree today!”

Hikers might also see lizards and snakes — but if you do, don’t panic: “For the most part, they are not interested in us at all. They just want to go about their snaky business,” Wallisch said. And if you see a white-tailed deer, you might notice that it appears smaller than deer in other regions but with bigger feet. “They adapted,” Wallisch said. “They evolved with those feet because it’s easier to walk on wet ground.”

The preserve is a great spot for birding too, especially in fall and spring as millions of birds head south to Central or South America for the winter, then return.

For tourists taking a side trip to the park from New Orleans, it’s interesting to consider that the preserve “is pretty much what New Orleans looked like” when European settlers arrived 300 years ago. The region’s swampy landscape and oppressive weather “may not be what we’d consider prime real estate,” Wallisch said, “but the location on the Mississippi River was so perfect they said, ‘We’ll just tough it out and build a city.'”q