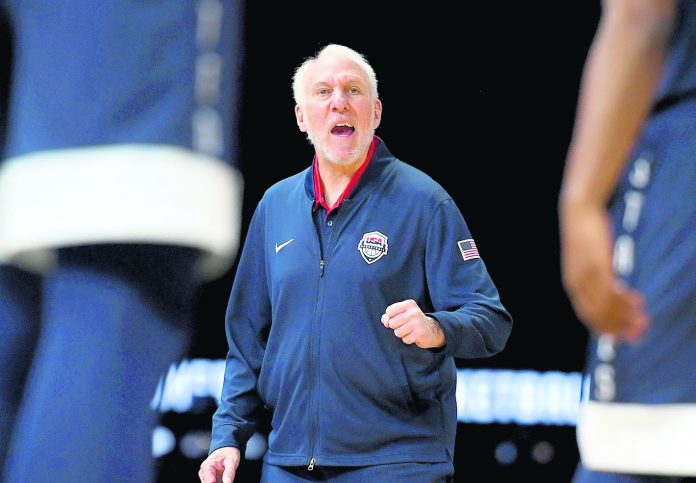

Even now, U.S coach Gregg Popovich remains a military man.

Nearly a half-century after his graduation from the U.S. Air Force Academy, it hasn’t been uncommon in recent San Antonio Spurs offseasons for Popovich to return for workouts on the wooded trails of that campus in Colorado. He’d be gasping thin air found at 7,700 feet above sea level, lungs heaving, mind racing.

As a student, he’d go there to think. As a graduate, he’s done the same.

“What you learn there is to get over yourself,” said Popovich, a five-time NBA champion coach with the Spurs. “It’s not about you.”

That is why Popovich’s first stint as coach of the U.S. men’s basketball team — it starts in earnest this weekend, when the Americans open their quest for a third consecutive basketball World Cup championship — has not become some sort of comeuppance tour for infamous previous attempts at gold that went awry.

As such, this World Cup isn’t about avenging the disappointment that Popovich still carries over getting cut from the 1972 U.S. Olympic team as a player despite having a stellar few days at tryouts for the team that lost a controversial gold-medal game to Russia. It isn’t about how the 2002 world championships team that he was an assistant on finished sixth, or how the 2004 Olympic team that he assisted managed only a bronze.

The Air Force Academy taught Popovich to focus on the current mission. Right now, and that’s guiding the U.S. to gold in the World Cup.

“Pop is completely locked in on this one thing,” USA Basketball managing director Jerry Colangelo said. “He understands what the goal is, what we’re playing for here.”

The Americans arrived in Shanghai on Thursday, with Popovich one of the first to greet some fans who waited at the team hotel and sign a couple dozen autographs. He took his time with each, carefully scripting the cursive, telling those who camped out on a rainy morning that there was no need to rush.

His team opens play Sunday against the Czech Republic, then faces Turkey and Japan later next week in the last two group-stage games. Getting out of group play shouldn’t be difficult; two of those four teams will move on to the round of 16. But a loss in an exhibition at Australia last week suggested that this U.S. team could be more than a little vulnerable against the other World Cup contenders.

Popovich has been telling his team that winning the World Cup will be tough. The loss only reaffirmed what he was saying.

“For a number of reasons, but ultimately the way he talks about us having these three U-S-A letters across our chest, we know what this means to him,” U.S. guard Joe Harris of the Brooklyn Nets said. “He obviously has a tremendous amount of pride and respect for his country and you can feel it in how he goes about his business. This isn’t something he’s just doing for the hell of it.”

Popovich’s backstory, at least the parts he wants to open up about, is well-chronicled. His undergraduate degree was in Soviet Studies. He considered a spy career and has gone through intelligence training. He’s not shy about bringing up his opinions on anything, and in recent years he hasn’t held back on political criticism.

Economic relations right now between the U.S. and China are thorny, at best. But when Popovich arrived Thursday, donning a blue jacket with the USA Basketball red, white and blue logo, the Chinese fans who came out to greet the Americans cheered him.

“It’s hard for me to speculate on what this means to him,” said Will Voigt, Popovich’s former video coordinator in San Antonio and now the coach of the Angolan team competing in this World Cup. “He is a man of principle. And especially in this day and age in our country, with everything going on, how Team USA represents the country is very important to him. Sometimes that gets lost.”

Popovich hasn’t shared much about his 1972 experience with his current U.S. team. He was one of about 60 players under consideration for the Olympic team that summer and shot the ball better than anyone there — he made 58 percent of his attempts — but never had a chance at getting picked for the squad. A committee was put together, plenty of politicking was happening and Popovich didn’t partake in the shenanigans.

So he got picked for an AAU team instead that played a series of international exhibitions. It wasn’t the same.

“The thing I always wanted to do was be on the Olympic team and play,” Popovich said. “That was always my dream.”

He’s been to the World Cup and Olympics as an assistant, but he’s now the man in charge. He’s replacing the most successful coach in U.S. history, Mike Krzyzewski, the Duke guru who led the U.S. to the last two World Cup titles and the last three Olympic golds.

Popovich took a few weeks to formally accept Colangelo’s invitation in 2015 to replace Krzyzewski in this cycle as national team coach for the World Cup and next year’s Olympics in Tokyo.

The delay probably wasn’t needed.

From the outset, Popovich felt compelled to jump at the chance to serve again.

“It’s impossible to separate it if you have been in the military,” Popovich said. “I’ve had classmates that have fought in wars — I have not — and some of them are no longer with us. You get an appreciation for people who have sacrificed. So when you have an opportunity to do this for your country, it’s impossible to say no. I love being part of it.”q