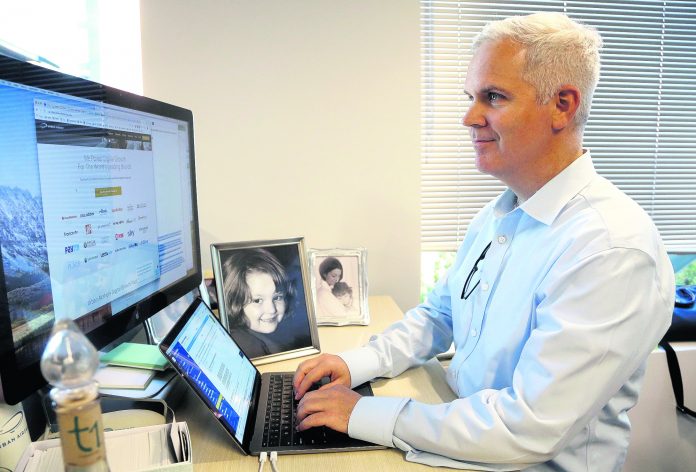

Like a lot of parents, Mike Herrick occasionally sees his 13-year-old daughter getting lost in her smartphone and wonders: Is technology messing with children’s brains, even as it enlightens and empowers them in ways that weren’t possible when his generation grew up?

What sets Herrick apart is his job. He is a product and engineering executive at Urban Airship, a company in Portland, Oregon, that makes online tools that send the kind of relentless notifications that can make people act like bears near a honey pot.

The tensions between the pride Herrick takes in his profession and his parental qualms about technology tug particularly hard when he sees his daughter, Lauren, and her friends texting each other instead of talking — when they’re sitting 5 feet apart. Or when he hears a friend jokingly describe him as a “mobile arms dealer.”

At times like those, Herrick worries that technology may be having a corrosive effect on society, even though he feels no regrets about his job because he unequivocally believes that Urban Airship’s tools are a net benefit to people.

“You can’t help but feel the juxtaposition,” says Herrick, 44. “The power of this age we live in is that it has given everyone access to all this information and the ability to stay connected to people, but how do we manage it better?”

It’s a question besetting other technology executives, too. Many say they’re trying to reconcile their fulfillment from working in a financially rewarding industry that they say has made life more efficient, enjoyable and affordable for people with their misgivings as parents about the addictiveness of devices and social media that now define much of daily life.

Technology “can be like opening your refrigerator door when you are hungry and just staring into the abyss,” says Keith Messick, chief marketing officer for Dialpad, a specialist in phone systems that incorporate voice controls and other artificial intelligence. “That’s when I recoil just a little bit.”

He is especially troubled when he sees his own 13-year-old son mindlessly thumb at his screen. Messick also worries that the ease of texting and posting on social media is turning kids into poor communicators who write things they’d never say in person or in a phone conversation — on the rare occasion when they use their devices to make a call.

“This is the world we live in,” Messick says. He says he still believes that technology’s “positives far outweigh the negatives.”

Most parents have similarly mixed feelings about technology, whether or not they work in the industry. About two-thirds of U.S. parents worry that their teenage children spend too much time immersed in a screen, according to a survey released in late August by the Pew Research Center. Nearly three-fourths of parents said they thought their teenagers were sometimes distracted by their phones during conversations with them.

Yet 86 percent of the parents say they’re very or somewhat confident that they have determined an appropriate amount of screen time for their teens. Slightly more than one-third of parents acknowledged spending too much time on their phones themselves, the survey said.

The concerns about children’s rising dependence on technology extend beyond parents. They sometimes also vex other relatives, like aunts and uncles. One of them is Apple CEO Tim Cook, who revealed in a public appearance this year that he tries to keep his nephew off social networks.

Apple is trying to address some of the problems it helped create with the 2007 introduction of the iPhone by offering more features for parents to monitor and control how much time they and their kids spend on the devices.

The new tools, part of the latest version of an iPhone operating system released last month, can even be deployed to keep kids off distracting apps like Facebook, Snap and Instagram completely — or just at certain times of day. Google included similar controls in its latest version of the Android operating system, which powers most of the world’s smartphones.

Instagram co-founder Kevin Systrom thinks that is a good idea. He is already vowing to limit his now-10-month-old daughter’s eventual exposure to devices and social media as she grows up.

At the same time, Systrom, 34, is hoping his daughter will embrace technology as he did when he began using computers and surfing the internet as a boy. He credits his own early fascination with technology for inspiring him to create Instagram — an app with more than 1 billion users whose success has rewarded him with an estimated personal fortune of $1.5 billion.

“Obviously, like anything — whether it’s food, or drink — moderation is key,” Systrom says. “I think we are in a world where we have to develop opinions on what that moderation is and how to do it.”

Brian Peterson, Dialpad’s co-founder and vice president of engineering, loves his job and technology, too — so much so that gave both his daughters iPads around the time they were 2.

It seemed fine at first, because they were using the tablets on instructional apps that helped them learn things like playing a virtual piano. But then he started to notice that the girls, who are now 6 and 4, seemed to be spending most of their iPad time watching YouTube videos of other kids playing with toys or doing something else that he and their mother wished they weren’t.

“That is when we had our freak-out moment and said, ‘Hold on a moment, no more of this drug,’ Peterson says.

Now, he has decided to hold off on getting his daughters smartphones until they reach middle-school age — or, even better, as presents when they graduate from high school and are ready to head off to college.

“I am just praying by the time that my kids really need a smartphone, they have really good parental controls, Peterson said.q