Booking a magical glimpse inside Etnia Nativa

Article by Etnia Nativa call us 592 2702 and book your experience!

Each week, Etnia Nativa presents a new episode about cultural heritage, native knowledge, and the responsibility to acknowledge heritage, traditions, and the limited space our tribe had living on an island. It’s sharing today a brief introduction to the history of how Aruba’s livelihood was before oil and tourism. Natives faced a constant existential adaptation since the Spanish era until the gold rush.

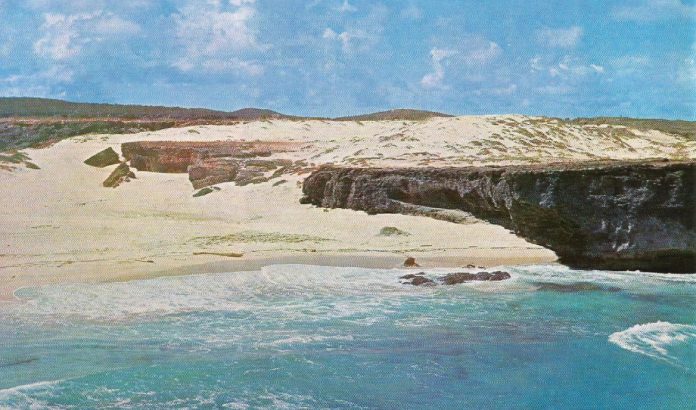

Aruba’s gainful economic life has known periods of dire extremes. There have been occasions of near famine as a result of net-to-no means of support since a great part of what the island could produce during good or bad times had to be shipped to Curacao. Periods of quick, short-lived prosperity and a stable economy based primarily on oil refining followed.

Under the Spanish regime during Aruba’s recorded beginning, tribal people busied themselves with many trades and crafts. Some of these endeavors had devastating results on the landscape, depleting the island almost completely of a particular tree for the export of Campeche wood, or its variety, Brasil wood. The wood, which grew in abundance on Aruba centuries ago, yielded a red dye used in the textile industry. Over a century of Spanish rule transformed Aruba into a large rancho. Goats, sheep, burros, cattle, and pigs were brought to the island, bred, and allowed to roam freely over the countryside. The animals ‘freedom undoubtedly came during the periods when the island went uninhabited by Europeans. The native Caquetios very often left Aruba for the mainland, today Venezuelan, since it was all part of their ancestral territory and tribal political land. It is reported that when the Dutch took over Curacao, the news ran fast, and many natives went into hiding or left Aruba, leaving the island almost uninhabited. After the Dutch promised to respect their land, boats, and animals, the Indians began to return to their villages in Aruba under Dutch rule.

During the Dutch era, means were proposed to develop an economic structure in the ABC islands. Aruba was to be the horse breeding farm; Curacao was the plantation island; and Bonaire was dedicated to the salt industry. The natives bred horses on the island, which, from the bay at Oranjestad, hence the name Paardenbaai (Horses ‘Bay), were sent to the mainland to be used for military purposes, mainly against the Spanish.

Until the mid-18th century, when a few privileged persons were allowed to settle in Aruba for trading purposes, the island’s economic life was little more than the trading of sheep, goats, flour, fruits, and water with marauding French, Spanish, English, and pirate ships.

Aruba’s history is void of slave trading. While Curacao grew to be a leading slave market in this trade, Aruba never became a point of exchange. It wasn’t until the Emancipation of 1863 that Africans came to Aruba, and then to seek employment.

The first mention of gold in Aruba occurred in 1725, when rumors of hidden wealth reached the West Indies Company’s home office in Holland. Quickly dispatched was Paulus Printz, a European miner. Although he never produced any gold, he reported the presence of metallic ores. Just about a century later, gold was found in Aruba. Naturally, legend covers the incident (see Episode 173). Accordingly, a 12-year-old youth tending his father’s sheep was stuck by a cactus needle while crossing a valley called Lagabai, near Rooi Fluit, a dry river bed. The lad bent down to remove the piercing barb, and in so doing, spied a shining object. It turned out to be gold—yes, pure Aruban gold.

It was alluvial gold, and nothing much was done about its recovery other than the island’s residents panning the streams. Between 1832 and 1846, some gold was extracted from deep quarries. In 1854, the first exclusive rights to exploit the minerals of Aruba were granted. Nothing much was done, however, which was pretty much the case until Jan van der Biest, an Aruban acting as superintendent of the Bushiribana works of the Aruba Island Gold Mining Co., Ltd. of London, extracted 2075 ounces of gold. The project died in 1882 when costs became prohibitive. Another company started in 1897 and failed shortly thereafter. It wasn’t until the Aruba Goud Maatschappij got under way in 1908 that profitable mining was conducted. It continued until World War I, when it cut off its supply of necessary materials. Gold was never mined successfully in Aruba again. Attempts were made to recover the previous material as late as 1947, but to no avail.

Interested in connecting and grounding yourself to your travel destination, living history, autochthonous art, and the island`s true identity? Then book a visit to Etnia Nativa. This is a unique peek into a local native gem! Let our acclaimed columnist lecture you through the most interesting hour. Aruban stories undiscovered—an adventure beyond beaches. Visit his magnificent dwelling, bursting with culture and island heritage! Whats App +297 592 2702 etnianativa03@gmail.com