Booking a magical glimpse inside Etnia Nativa

Article by Etnia Nativa call us 592 2702 and book your experience!

Each week, Etnia Nativa presents a new episode about cultural heritage, focusing on native knowledge and the importance of defending the true identity of Aruba. During this episode, we share a brief history of how the city of Oranjestad came to be.

The first buildings in Oranjestad were erected in late 1797; it became a little town in less than thirty years. Its houses were anything but large, and all of them were on one floor; some had an attic, except the commander’s house, which had two stories, an attic, and a second floor with a balcony facing the bay.

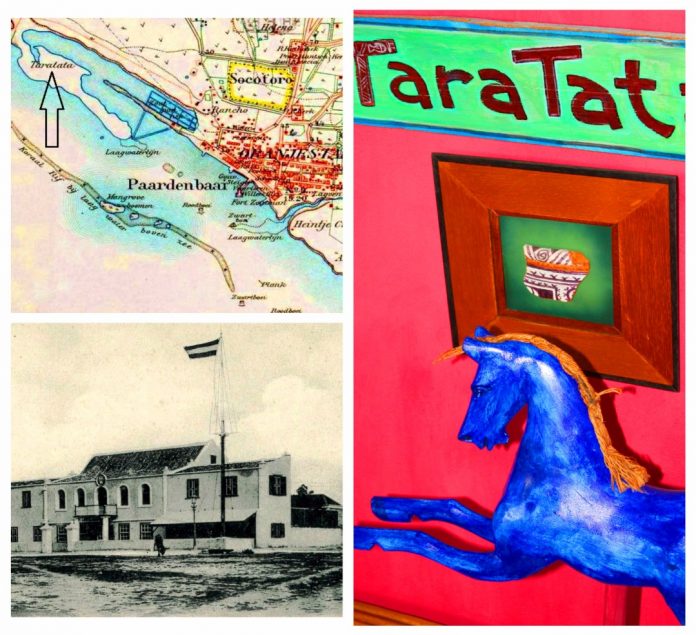

Upon the completion of Fort Zoutman in 1797, white native Protestants gradually started building their stone houses at Ponton that offered a strategic view over the south and west coasts of the island. But in those days, without motorized transportation or a proper paved road, it was a bit too far from the site where ships laid anchor. At the beginning of 1797—we know this accurately—there was not a single house at Paardenbaai. Eight years later, therefore, in 1805, there were as many as 32.

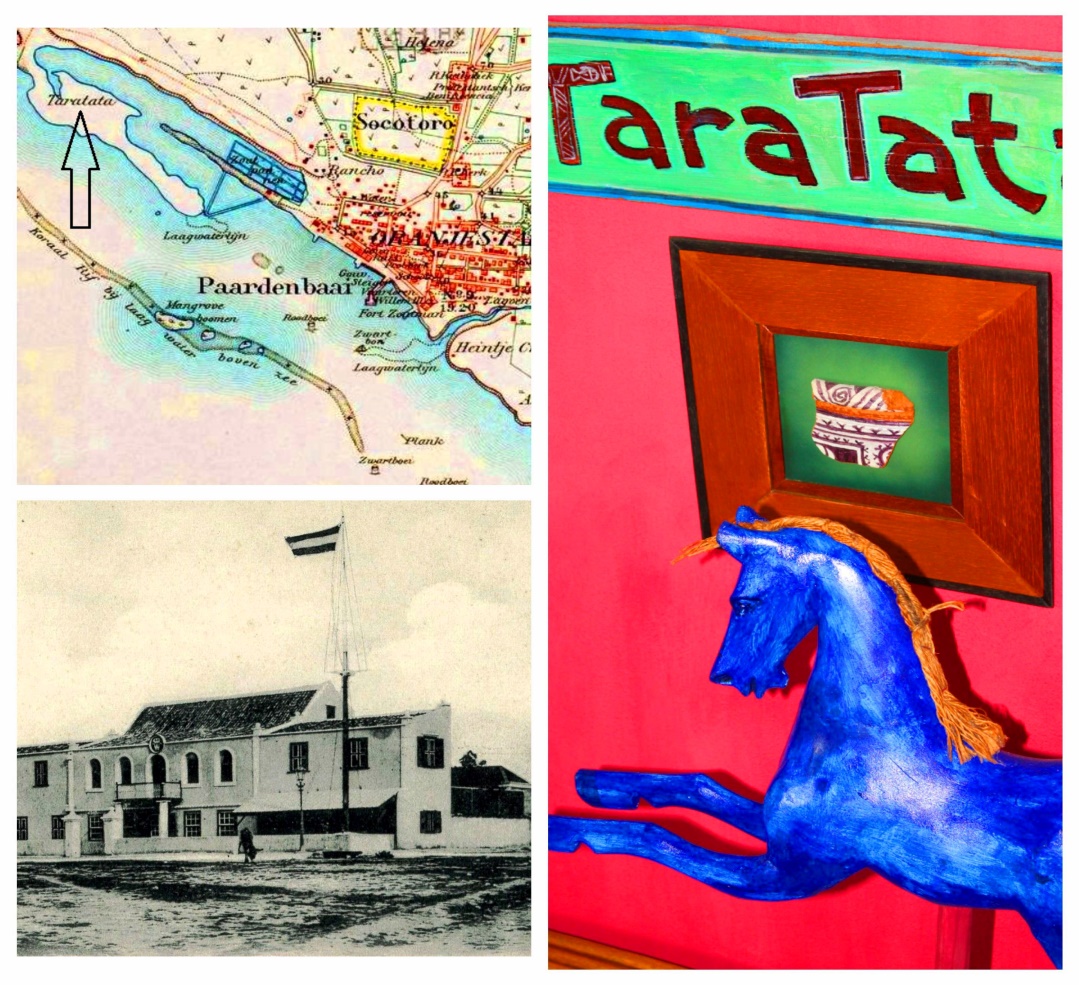

The ships arrived at Paardenbaai, the Bay of Horses, named by the Spaniards, who used an area called TaraTata by the natives to import horses. Tara Tata, a name derived from the Paleo language, refers to primitive or Stone Age inhabitants. For them, TaraTata meant a place of arrival, since there was a beach in between the mangrove forest that covered most of the rocky coast line going east toward Savaneta. On the other side of the coast, on the continent—actually, Venezuela—there was a place called TaraTara, meaning place of departure.

Concerning the building of houses; there were specific rules in effect that one should consider when constructing a house in those days close to the bay; there had to be an open space of not less than 800 paces between the fort and the nearest-located building of the city, the so-called esplanade.

As soon as tiles were introduced, several roofs were entirely covered with them, and the dwellings of the less-good-to-do had roofs constructed of maize stalks or palm leaves, while the traditional natives had their sturdy but effective mud mixture roof, well known as “torto.” The construction of cottages of this kind consisted mostly of a pre-woven structure made out of sticks, branches, and small timber. Stone or brick houses of the period were almost all white-washed, the tiled roofs being deep orange. Some fresh dwellings are provided with a rainwater collection system and a dug-out well.

The growth of the town had almost come to a stop after thirty years. In 1827, the town had been divided into an eastern and western half. The eastern half toward Dakota numbered 77 houses in 1837, of which 33 were brick ones. It appeared that the more fashionable quarter was to be found in the part of the town closest to Dakota. Almost half of the houses in this area were made out of local bricks.

The houses in Oranjestad were built in a very disorderly fashion, in spite of the 1822 regulation. Buildings were sometimes placed at less than fifty yards’ distance from the cannon on Fort Zoutman, effectively preventing the garrison from opining fire on any ship or object in the bay without firing right into them. There was even a house thirty meters from this stronghold,” making it impossible to dominate the countryside in times of unrest.

The roads were bad and pock-marked with holes. In the evening, it was impossible to pick one’s way through the maze of houses scattered about in haphazard fashion without coming a cropper, as there was no illumination. Finally, in 1827, one regulation ordered everyone to clean the roads around their houses and to clear away loose rocks. However, inside the town, cattle and livestock in general roamed about at will, while pigs were rooting up the unpaved streets. Not before the close of the 19th century did what are now Nassau Street and Wilhelmina Street get a few hundred yards of pavement consisting of what the Dutch call babies’ heads, i.e., cobbles.

Would you like to know a little more about Aruba’s origins, cultural influences, and more? So Etnia Nativa is a thematic encounter for you. Be one of the exclusive visitors to a private residential setting housing an assemblage of native art, archaeological artifacts, colonial furniture, and other items belonging to the first Oranjestad’s families. Let Etnia Nativa guide and lecture you towards the most interesting and revealing native Aruban stories, undiscovering the island’s life beyond beaches.

Whats App +297 592 2702 etnianativa03@gmail.com