Etnia Nativa writes Island-Insight, focusing on various aspects of native knowledge, transcendental wisdom, and the importance of upholding cultural identity. This column aims to educate its readers and encourage them to embrace a genuine island state of mind. In this episode, Etnia Nativa shares the beginnings of education in Aruba.

The first inhabitants of Aruba were animists and practiced various forms of worship and belief systems. When the Spanish conquerors arrived, the native inhabitants were subjected to colonization and efforts to Christianize them. The exact timeline of the conversion process is not well documented, but historical evidence suggests that Juan Manuel Martinez de Manzanillo, bishop of Caracas, Curacao, Bonaire, and Aruba, visited our island around 1593 to perform the Sacrament of Confirmation. This indicates that the conversion had already started before this period.

However, there was no permanent church building in Aruba until the arrival of the Dutch in 1636. The Dutch occupation complicated matters further, as they forbade visits from priests from the continent, and in 1639, the Dutch West Indian Company formally instituted a prohibition on the Roman Catholic religion.

Overall, a combination of Spanish and Dutch influence marked the history of religious conversion in Aruba, alongside the persistence of Catholic priests who maintained contact with the local population despite official prohibitions.

During 1700s, the descendants of Spaniards and indigenous people formed a settlement in an area that is now known as Alto Vista. They conducted their religious services in different houses until a chapel, was constructed in 1750.

Since there were no permanent priests available, fiscals (lay officials) were appointed to oversee the religious affairs of the community. The first known fiscal was Domingo Antonio Silvestre, followed by Miguel Enrique Alvarez. The mention of their ability to read and write is significant because it indicates the beginning of education during that time. They had the responsibility to teach others. This suggests that education has started to emerge in the community.

Under the leadership of the fiscal, the church at Alto Vista was eventually abandoned, and a new church was constructed in North (Noord), which later became known as St. Anna. It is worth noting that around 1780, a shipwreck caused an epidemic known as the black fever or death, resulting in the loss of a significant part of the settlement’s population. Both the Church and the Government believed that the people should relocate to a healthier area.

The present Alto Vista chapel was built close to the same site where the first church stood. The chapel houses an authentic and original cross that was saved from the first church. A descendant of a former church member donated the cross. Additionally, there are a couple of graves in the chapel yard, where the first fiscals were buried shortly after the opening of the first church in North.

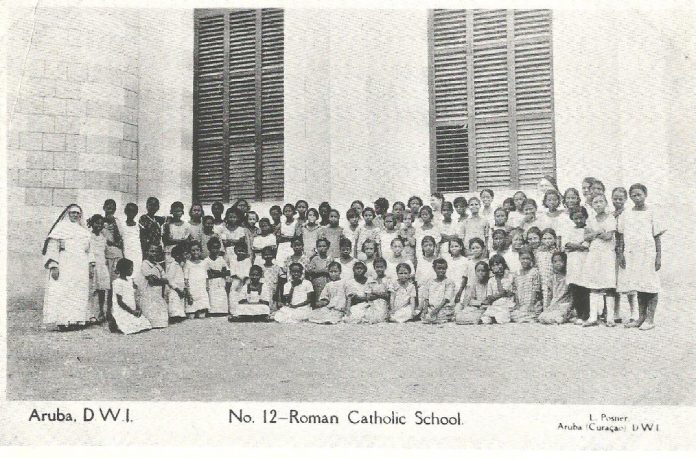

By 1825, there were two schools on the island. The public school offered Protestant teaching in Dutch, while the Roman Catholic school provided education in Spanish. In the late 1800s, nuns arrived and took on teaching duties until 1909.

By 1875, there were schools in Oranjestad, North, and Santa Cruz. Interestingly, only Dutch was taught in Oranjestad, both in the public and Roman Catholic schools. In North and Santa Cruz, Papiamento, the local language, replaced Spanish. By the turn of the century, a school in Sabaneta taught in Papiamento. In 1899, a small Protestant school in Piedra Plat had already been established, although it did not expand significantly. In the 20th century, education began to firmly establish itself, and parish schools received adequate subsidies and legal recognition.

By 1916, there were schools in North, Santa Cruz, Sabaneta, and Oranjestad. These included one government/public school, one for girls, and one for boys, providing education up to the 6th grade. After 1916, two more grades were added (U.L.O.), and in 1938, MULO (a 10-grade program) became the standard for Oranjestad schools.

In 1924, the oil industry arrived, with companies like Eagle and Lago Petroleum Corporation. Lago started an apprentice program in 1935 to teach young men English and trade skills in preparation for work within the refinery. Aruba’s first trade school was established in 1952.

Prior to the arrival of the oil industry, Aruba was predominantly Catholic, with a presence of Dutch Reformed Protestants and Jews who did not have an official place of worship. However, with the establishment of refineries immigrants from approximately 40 different nationalities settled on the island. Churches of various denominations were established, particularly in and around San Nicolas. However, these denominations did not introduce their own schools or schooling systems. Lago, on the other hand, constructed a school following American standards for the children of its employees.

We highly recommend visiting Etnia Nativa on site if you have a keen interest in experiencing Aruban native culture. The owner’s first-hand knowledge and explanations add authenticity to the experience, immersing you in Aruba’s rich history and cultural heritage. The place is an incredible “cabinet of curiosities.”

To arrange a visit, contact etnianativa03@gmail.com or WhatsApp (messages only) at +297 592 2702. Appointments are necessary to ensure a personalized and immersive experience.