Booking a magical glimpse inside Etnia Nativa

Our narratives have long emphasized the vital balance needed in all that we do, especially on a small island like Aruba. For generations, we thrived with a laid-back colonial existence, shaped by a unique blend of cultures. However, the neglect of our cultural heritage and the growing threats to our biodiversity has reached critical levels.

This platform is dedicated to preserving and rediscovering native traditions, while exploring the true spirit of what it means to be Aruban and reflecting on our history and identity.

During this episode, we provide a brief historical overview of the evolution of drinking water in Aruba, highlighting its importance as a basic necessity for the establishment of human populations. Therefore, it is no surprise that, in arid regions like ours, people have sought ways to desalinate brackish or seawater to produce drinking water for centuries.

Before the establishment of the current seawater desalination plant, the native population relied on collected rainwater for drinking. They had limited access to natural fresh water, finding it in a few places such as caves where water leaked from stalagmites, springs like Loran, also known as Pos di Rey, located on top of a hill near Shette, and under rocks at Paraboste, among others.

Rainfall in Aruba typically occurs from August to February during the rainy season, but most of this rainwater quickly flows to the sea through dry riverbeds. In some areas, natives dug dams and irrigation channels, which were covered by vegetation such as Kwihi and other trees to prevent evaporation, like those at Tanki Flip. During the early colonial era, rainwater was also collected from the surface for use in homes and small-scale livestock farming.

While surface water can be abundant during the rainy season, it quickly dries up in the dry season, becoming scarce due to evaporation and absorption by the porous layers of the soil. Rainwater that filters through these layers accumulates in aquifers and underground channels, forming what are known as underground rivers. On Aruba’s northeast coast, a small stream called Fontein flows year-round with crystal-clear water, in contrast to ephemeral streams that only flow after heavy rains. Historically, Fontein’s water was used for horticulture and later by a group of Chinese families who grew vegetables. However, the stream’s flow has been hampered due to excessive dynamiting of nearby limestone quarries for commercial extraction.

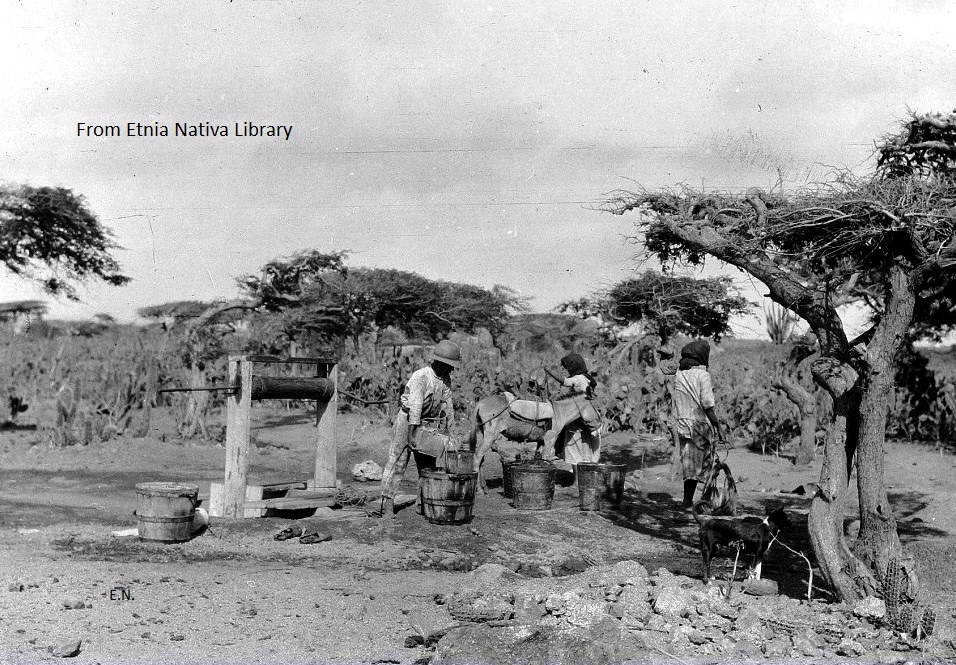

Wells of varying depths were dug by hand using chisels and hammers throughout the island to access groundwater. Due to the dissolution of minerals and calcium carbonates in some of these wells, the extracted water has a certain level of salinity and is known as ‘brackish water.’

Water from the well was extracted manually using a wooden bucket tied to a rope. Later, windmills with wooden or metal frames were installed to pump water to the surface. Meanwhile, the island’s early inhabitants, the Caquetio Amerindians, established their villages in areas where water and food were available. They would dig small holes near beaches to access naturally filtered seawater for drinking, a practice that became an art.

With low rainfall, scarce natural freshwater sources, and limited groundwater reserves, Aruba faced a significant water shortage for the gold industry following the establishment of the Gold Mining Company in 1899. This shortage led to the decision to build a melting plant in Balashi and desalinate seawater from the nearby Spanish Lagoon.

During the colonial era, houses were built with cisterns to efficiently store rainwater, improving its quality for consumption and domestic use. At that time, peeled cactus plants were used as a natural coagulant or filter for muddy water.

When Petroleum refining company was established on the island, a solution was needed for both drinking and industrial water supplies. Initially, it was decided to import drinking water from the United States using special tankers. However, this system proved inadequate. As a result, a new water supply system was implemented for Oranjestad and St. Nicholas, distributing distilled and mineralized water—a system that had already proven successful in Curaçao. (Episode 216:Drinking water in Aruba)

If you enjoyed reading our stories and are interested in learning more about the island’s true identity, we recommend booking a visit to Etnia Nativa—the only ‘living museum of its kind in the Caribbean.’ Since 1994, Etnia Nativa has been a trendsetter and a co-founder of Aruba’s National Park, the Archaeological Museum Aruba, many Artisan Foundations, and other organizations. Etnia Nativa offers valuable knowledge and connects you to the ancient spirit and soul of the island. Contact by WhatsApp+297 592 2702 oretnianativa03@gmail.com.Visits are private and by appointment only.