Booking a magical glimpse inside Etnia Nativa

Article by Etnia Nativa call us 592 2702 and book your experience!

The narrative shared through Etnia Nativa, which means native ethnicity, emphasizes the importance of reclaiming and recognizing the island’s cultural roots and heritage, which have often been overshadowed by colonial history. The entity actively engages in promoting the value of rediscovering native traditions, history and identities, while highlighting the importance of moving beyond colonial influences or submissive behavior.

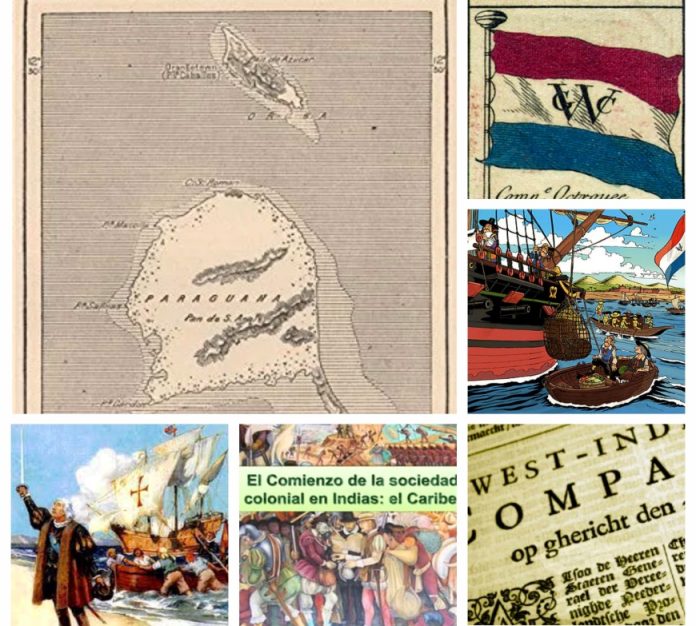

A significant theme is the acknowledgment of the persistent colonial legacy in Aruba, which continues to shape the collective mindset. The influence of both Spanish and Dutch colonialism on Aruba and the broader Caribbean region is crucial for understanding how educational systems and ideologies have been influenced by these colonial powers. The way historical narratives are often framed through the lens of the colonizers resulting in a skewed perception of the past, one that needs to be challenged for a more authentic understanding.

Etnia Nativa reflects on the contrasting realities under the Spanish and Dutch colonial regimes. Under Spanish rule, indigenous peoples enjoyed some political recognition, as Spain treated their kingdoms as equal to those of Europe. However, this acknowledgment was far from the lived reality, where natives were still subjected to exploitation, or forced labor, and various forms of violence through systems like encomienda; a so-called grant by the Spanish Crown to colonists in America conferring the right to demand tribute and forced labor from the Indian inhabitants of an area.

Under Dutch rule, the situation for indigenous people was legally different. The Dutch colonial system theoretically provided indigenous peoples with rights as free citizens, not subject to the brutal enslavement practices seen under the Spanish. However, the gap between legal rights and the lived experience of the indigenous populations persisted. While there were some protections in place, these were often undermined by exploitation and severe deprivation. The indigenous populations were theoretically protected from enslavement, yet they faced other forms of systemic oppression.

The work of Etnia Nativa in shedding light on these contrasting historical narratives serves a dual purpose: not only does it honor the resilience and history of our island’s native inhabitants, but it also strives to contribute to a more honest and inclusive discussion about Aruba’s identity and its future, moving away from colonial narratives and practices that have long shaped the island’s cultural and social structures.

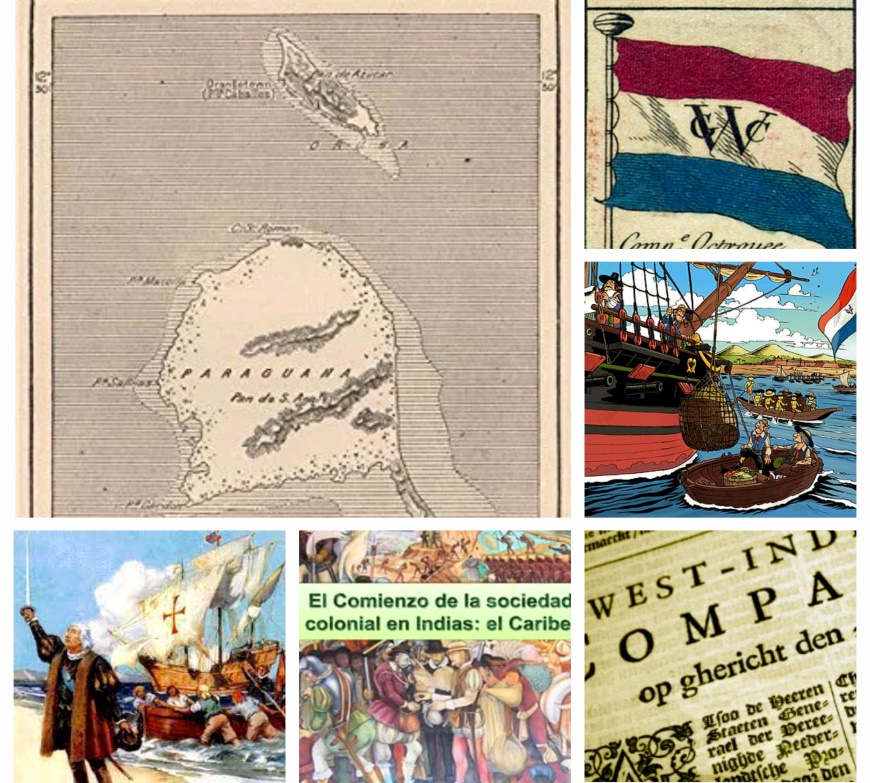

In 1635, the Dutch West India Company employed some indigenous people as hunting servants. In exchange for their labor, they were given basic provisions such as clothing, shoes, and, for the first time, full rations of bread and “agua ardiente” (a type of alcohol). Although these individuals were officially considered “free,” their living conditions were harsh, and their freedom was severely limited by the economic and social structures of the time. Their status, though legally not enslaved, was shaped by the demands of the colonial economy.

A court case from around 1804 in Aruba sheds light on the restrictions placed on the indigenous population. It concluded that while indigenous people were allowed to raise goats and sheep, they were prohibited from raising donkeys, horses, or cows. This limitation suggests that their economic autonomy was tightly controlled, as the colonial authorities sought to regulate and restrict indigenous involvement in certain economic activities.

Moreover, Aruba, Curaçao, and Bonaire hosted a population of “red slaves”—indigenous people who had been captured in conflicts on the mainland and brought to the islands by tribal chiefs. These captives, often young children, were taken during times of war and served various roles within the colonial economy. By the 19th century, many of these individuals were living on the islands, speaking their native languages, and continuing to be marginalized in the colonial social hierarchy.

The Dutch West India Company issued instructions aimed at “civilizing” the indigenous people. These instructions emphasized converting them to Christianity and promoting a “decent” lifestyle, which the Company defined according to European norms. The education of indigenous children was particularly emphasized, as the Company sought to change what it considered “barbaric practices” through efforts to encourage agricultural work, fishing, or other forms of labor. Idleness was viewed as a vice, and the Company believed that engaging indigenous people in work would prevent them from falling into what they saw as undesirable behaviors.

Thus, while Dutch rule theoretically offered legal protections for indigenous people—prohibiting their enslavement—the reality was far more complicated.

If you enjoyed reading our stories and are interested in learning more regarding the true identity of the island, we recommend you to book a visit to Etnia Nativa—the only “living museum of its kind in the Caribbean”—a fascinating choice, a trend-setter since 1994 and co-founder of Islands National Park, Archaeological Museum Aruba and Artisan Foundation among others. Etnia Nativa shares valuable knowledge and connects you to the ancient island’s spirit and soul. Whats App +297 592 2702 etnianativa03@gmail.com