Booking a magical glimpse inside Etnia Nativa

Article by Etnia Nativa call us 592 2702 and book your experience!

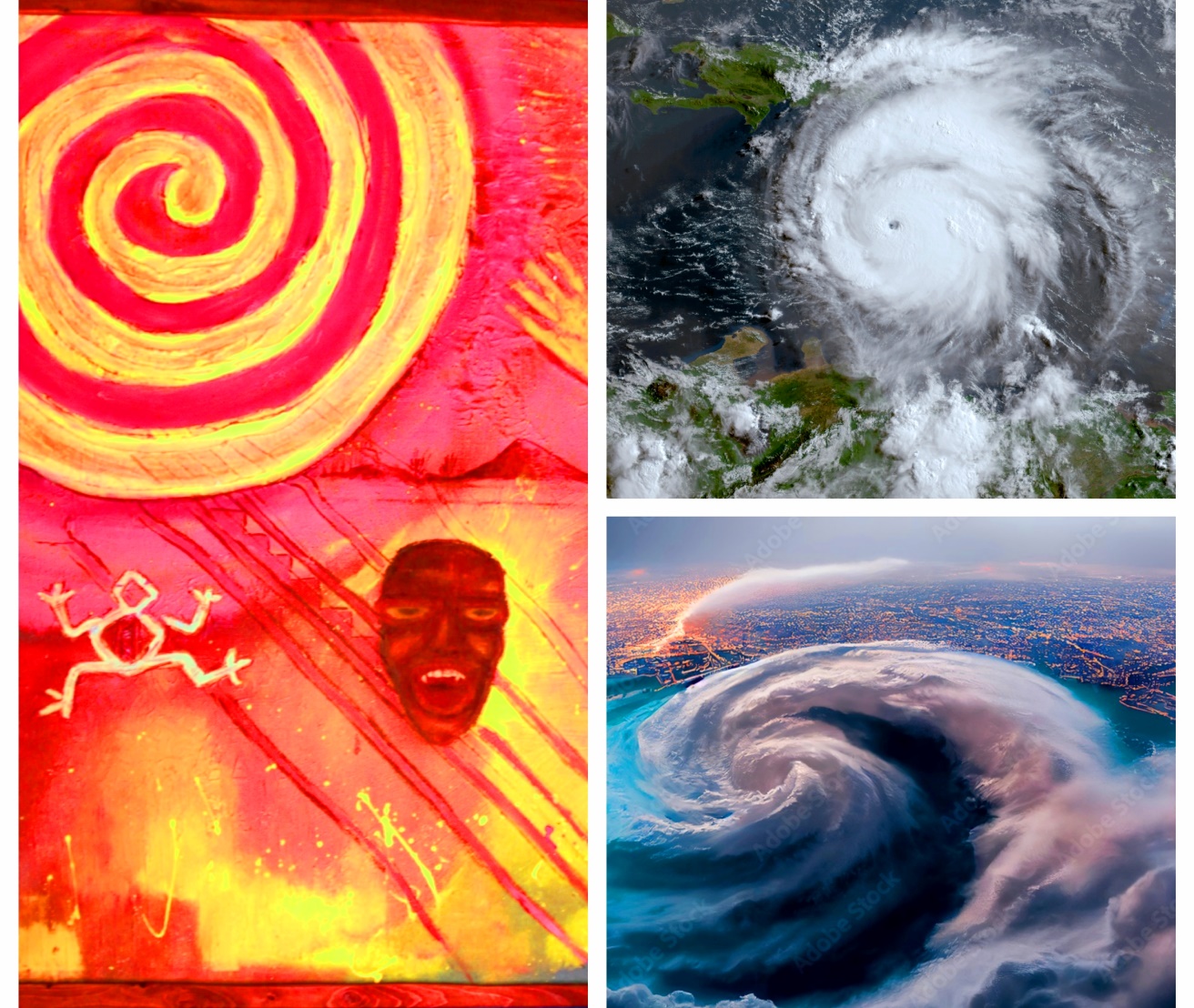

Every week, Etnia Nativa presents a new episode about cultural heritage and native knowledge. This week, it is about hurricanes. The recent onset of the 2024 hurricane season serves as a constant reminder and frequent topic of conversation. However, we can be grateful that our “privilege” close location to the South American continent spares the island from their devastating effects, and what we can get in Aruba is a lot of rain and thunderstorms.

When European sailors anchored their ships in the Caribbean Sea, they did not know what natural phenomena threatened the region. They only knew that the meteorology of the place presented different characteristics, so much so that ignorance and lack of experience were the main causes of the shipwrecks that occurred in the first years of intercontinental voyages.

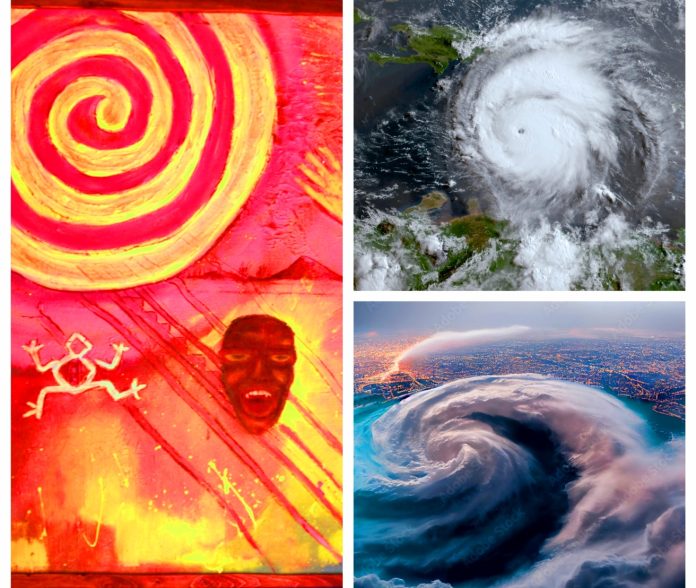

However, the civilizations that inhabited these places knew very well that, during certain times of the year and following the position of the stars, a superior natural force on their way was capable of destroying everything and menacing their survival. These Caribbean populations shared a word in common that identified the aggressive spirit behind the storms, known as huracan. Aruban Caquetian ancestors called it “horcan,” a word still used in our Papiamento language, meaning hurricane. They were animists, believing in the power of natural spirits that had a good or a bad effect on their existence in the form of rain, wind, sun, stars, and other natural forces that could do them good but also evil and so influence directly their lives: like when fears of winds show their anger, destroying their houses,*cunucos (agricultural fields), and tearing down huge trees.”

Some of these native communities represented the hurricane in the form of a spiral or a snake with swirling shapes. To interpret the movement of the hurricane’s rotation and its calm central part, which was its eye, surrounded by powerful winds that swirled counterclockwise, rotation creates the idea that it was a living entity that or mysteriously moved through supernatural forces, spinning from one cardinal point to the next. Once in a while, it barely advances its trajectory by a few kilometers and sometimes is static, attacking and devouring its victims.

The hurricane, just as it currently still does today, affects the economies of the towns it reaches. In most cases, those affected are not only dependent on tourism but also on agriculture for their existence. It is an unfortunate phenomenon that reoccurs every year and will continue to influence daily life in the Caribbean.

We need rain and gentle wind for the natural balance of our environment and cannot move or change our geography, but rather know, understand, and overcome the attacks of this phenomenon by building back better. Our ancestors sought explanations for the devastating phenomenon of observing the stars, the clouds, the sounds of some animals, or the strange calm that sometimes radiates from the Caribbean Sea before a storm.

There is controversy over whether the origin of the word hurricane is Taíno, Mayan, or Caquetio. For the Mayans, the hurricane was the god of the wind, and its syllables mean “hu-wind, ra-energy that gives shape, can-center,” translating the word as “wind concentrator.” For the Tainos and the Caquetios, the word hurricane simply meant “storm.” The word came to the English language directly from Spanish, when Spanish explorers took it from the Taínos and later from the Caquetios. It was quickly incorporated into many old-world languages since winds as strong as those of the Caribbean hurricanes were an unusual phenomenon for them.

At the time the Spanish language adopted this word, h was pronounced as f. So the same word in Portuguese became furacão, and in the late 16th century, the English word was sometimes spelled “forcane.” Many other spellings were used until the word became firmly established when Shakespeare used the spelling “hurricane” to refer to a waterspout. In Spanish and English, the word can be used to figuratively refer to anything that is powerful and causes confusion. In Spanish, hurricane can also be used to refer to a particularly impetuous person.

If you are interested in learning the true identity of Aruba, book a visit to Etnia Nativa, home of our chief cultural columnist, who has been a trend setter since 1994, having the honor to participate in the realization of the island’s projects such as the National Park and Archaeological Museum, among others. Actually, he continues to share the culture of Aruba, providing valuable knowledge to his visitors.

This private museum sets itself apart by offering a personal native touch and providing the opportunity to enjoy a diverse array of artworks, objects, artifacts, dead dissected animals, plants, colonial furniture, unique old photos, etc. Your opportunity to dive to the navel of Aruba! Whats App +297 592 2702 etnianativa03@gmail.com