By SARAH DiLORENZO

Associated Press

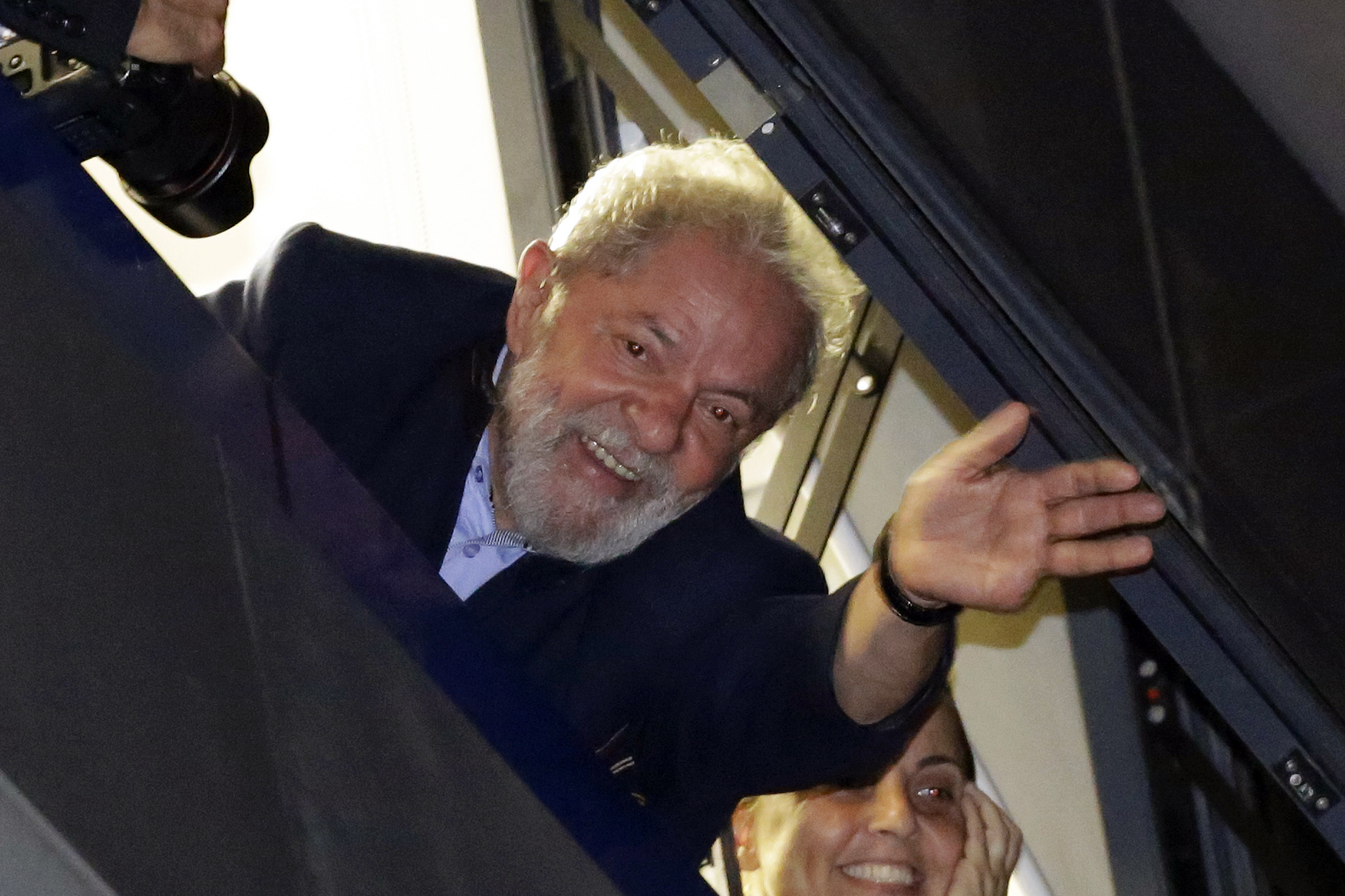

SAO PAULO (AP) — He’s tweeting about the politics of the day. He’s offered commentary on the World Cup. And he’s leading polls for October’s presidential election. Yes, he’s still in jail. Former Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva — universally known as Lula — has not faded from the headlines during his three months behind bars. Instead, analysts say his public profile is part of a risky strategy to attract attention and voters to his Workers’ Party — even if the ex-president himself is not ultimately on the ballot.

“The more time the (Workers’ Party) spends doing this, the less time there will be for another candidate to gain name recognition, to travel the country as the candidate,” said Oliver Stuenkel, a professor of international relations at the Fundacao Getulio Vargas university in Sao Paulo. The Workers’ Party publicly maintains there is no Plan B: They say da Silva’s conviction last year on corruption charges related to the country’s sprawling Car Wash investigation was unjust, and they intend to register his candidacy in August, despite a law that bars candidates who have had a conviction upheld.

Jose Crispiniano, a spokesman for da Silva, contends the law allows candidates with pending appeals to run for office. The Superior Electoral Tribunal will make the final decision and is considered unlikely to issue a ruling favorable to him. In the meantime, though, da Silva seems to be everywhere. Every few days, his aides post messages from him on his Twitter account. In one recent tweet, for example, he questioned whether the government had “any notion of the suffering of a father or mother who can’t provide sustenance for his or her family.” In another, he criticized a government privatization plan as selling “the country in a liquidation sale, without a care for tomorrow.”

Lately, the account has promoted his Instagram profile and a new YouTube page, although his influence extends well beyond social media. During the World Cup, he wrote commentaries that were read out on a TV station allied with his party. Supporters can also download a paper mask of his face from his website or learn from a video how to say “Lula” in sign language. The media blitz appears to have two goals, said Vitor Oliveira, director of analysis at Pulso Publico, a political consulting firm. The first is the hope that keeping da Silva as the candidate for as long as possible will increase the chances that voters will throw their support to another candidate of da Silva’s choosing, if he is barred from running.

The second is the bet that building excitement around da Silva could help in elections for the lower house of Congress, where voters can choose a party rather than a specific candidate.

Much of the fanfare may be preaching to the converted, and Crispiniano, the spokesman, notes that da Silva’s allies have no control over whether or how the Brazilian press covers the former president. But last week, da Silva commanded the nation’s attention for an entire day as a judicial battle unfolded over whether he should be released from jail. The president of an appeals court finally stepped in and decided he should remain incarcerated after dramatic back-and-forth rulings issued by different judges.

That chaos may have further bolstered the Workers’ Party’s narrative that the judiciary is unfairly targeting da Silva, Oliveira said. “The voter who is unsure … who maybe has sympathy with the Workers’ Party, with Lula, but who is not content, maybe you put a bug in this person’s ear,” said Oliveira. “This person is thinking about voting for the Workers’ Party again.” Then again, the turmoil on display during the fight over whether to release da Silva could unintentionally push voters into the arms of far-right congressman Jair Bolsonaro, who is running in distant second and promises to clean house.

“There’s a sense that people are tired, this entire apparatus is broken, everybody just acts in their own self-interest,” said Stuenkel. He said that some voters might ultimately think: “‘Our country’s rudderless, we need someone who shows us how to get out of this very difficult situation.'” For now, da Silva continues to be in the spotlight. After another judicial ruling last week that said he can’t give interviews from jail or record campaign material, his social media accounts posted a previously unreleased interview conducted before he was incarcerated and promised there were more to come.