By BRETT MARTEL

AP Sports Writer

NEW ORLEANS (AP) — Hall of Famer Andre Dawson sees elements of his own story in the black college players converging in New Orleans this week for a tournament sponsored, promoted and broadcast nationally by Major League Baseball.

Before Dawson’s two-decade career with the Montreal Expos and Chicago Cubs, he was a walk-on at Florida A&M. Scouts who’d been watching Dawson “disappeared” after his knee injury in high school, he recalled, but enrolling at a Historically Black College or University helped him keep playing.

“That’s what these programs do,” Dawson said, adding that HBCUs like his alma mater “were the ones that really extended me that opportunity.”

There’s one considerable difference between now and the early 1970s, however. The talent pool from which black college programs primarily recruit has shrunk as football and basketball have grown in popularity, particularly in urban areas.

As part of an effort the address that, MLB has sponsored a now decade-old tournament designed to highlight HBCU baseball programs, hoping to lure young black athletes back to the sport of Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays and Hank Aaron.

The tournament has yet to feature a single player who wound up in the big leagues, but MLB shows no signs of reducing its investment in the event — or in the urban youth academies around the country that are meant to provide inner-city youth with year-round places to train and play.

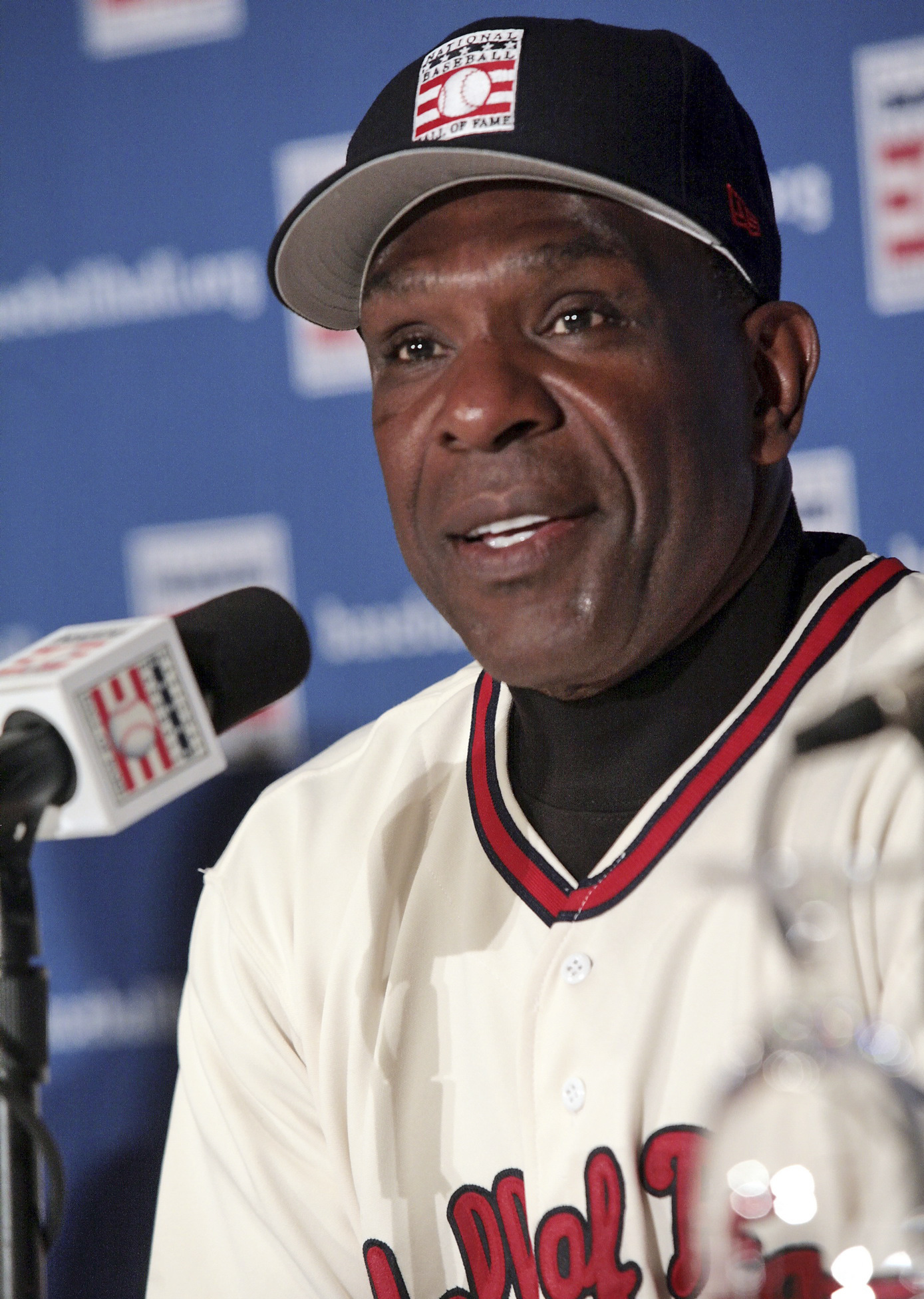

Last week, the tournament formally known as the Urban Invitational was renamed the Andre Dawson Classic. This weekend, it’ll feature six HBCUs: Alabama State, Alcorn State, Arkansas-Pine Bluff, Grambling State, Prairie View A&M and Southern. The University of New Orleans, which is helping to host the event with the New Orleans MLB Youth Academy, also will play, along with Illinois-Chicago.

For now, the tournament’s legacy is embodied by former HBCU players such as Earl Burl, who played for Alcorn State and did some of his training at the New Orleans MLB Youth Academy. He was a 30th-round draft choice by the Toronto Blue Jays in 2015. He spent two years in Toronto’s minor league system, followed by a short stint in an independent league. Now, he’s involved in a MLB fellowship program training him for a potential front-office career.

Burl asserts that the tournament changed his life.

“If you have a great game, it’s going to be seen by somebody,” Burl said. “A lot of scouts now-a-days do a lot of video analyzing. So being put on the radar that way is a good cornerstone” for building a reputation with scouts.

“It hasn’t produced a major league baseball player, but my thing is, someone’s always keeping their foot in the door,” Burl added. “So I feel like the more you have this, the further you’ll have people going in the game.”

Meanwhile, MLB’s efforts to raise the profile of the tournament on MLB Network and online attempts to address some of baseball’s perception problems among young black athletes, Burl said.

“If you’re not seeing people who look like you playing, it’s not something that you’re going to gravitate to,” Burl said. “It gives you that misconception that it’s not for you.”

Similarly, Prairie View coach Auntwan Riggins said MLB’s ability to promote the tournament its youth academies provides young black athletes role models and examples of people who parlayed youth baseball into full or partial college scholarships.

“Baseball is a very, very hard sport to market to kids of color because you see a LeBron James, or see football players on TV and shoe deals and commercials,” Riggins said, noting that football was his favorite sport growing up. But Riggins played baseball, too, and found out he was rather good at it. He play baseball for Texas Southern, was drafted by Toronto and later wound up within San Diego’s minor league system, making it as far as Triple-A with the Portland Beavers.

Riggins said he also sees an additional opportunity for baseball to make inroads with children of parents who are concerned about concussion data surrounding football.

“The percentage (of blacks playing baseball) will go up,” Riggins predicted. “I don’t think it’ll go up as fast as we want, but in due time it’ll go up.”

Tony Reagins, MLB’s senior vice president of youth programs and the Angels’ former general manager, contends that the Andre Dawson Classic doesn’t necessarily have to produce big leaguers to help the game.

“It would be great to see more of these kids reach the majors, but it is just as gratifying to help them get an education,” Reagins said. “There’s no doubt that we have seen the decline in participation of black players at the collegiate level, but I think our sport is doing a better job of getting more talented players recruited and signed to (HBCU) programs.

“Where this exposure takes the individual players is up to them, but we are proud to make the investment in creating opportunities like this.”

For Dawson, who played in a youth league organized by his uncle, the college tournament named for him will succeed as long as it inspires greater participation by young blacks in MLB academies or youth leagues around the country. Performing in baseball requires refining skills over time, which is why it can be hard to take up cold in high school with much success.

“As blacks, we’ve got to be embraced again — and it starts from early on,” Dawson said. “You’ve got to start at an early age and be encouraged. … You don’t want to put yourself in a potentially embarrassing situation where you’re set up to fail. It’s not going to be fun, and if you’re not enjoying it, you’re not going to want to do it.”