By MICHAEL RUBINKAM

Associated Press

INDIANA, Pa. (AP) — A library without books? Not quite, but as students abandon the stacks in favor of online reference material, university libraries are unloading millions of unread volumes in a nationwide purge that has some print-loving scholars deeply unsettled.

Libraries are putting books in storage, contracting with resellers or simply recycling them. An increasing number of books exist in the cloud, and libraries are banding together to ensure print copies are retained by someone, somewhere. Still, that doesn’t always sit well with academics who practically live in the library and argue that large, readily available print collections are vital to research.

“It’s not entirely comfortable for anyone,” said Rick Lugg, executive director of OCLC Sustainable Collection Services, which helps libraries analyze their holdings. “But absent endless resources to handle this stuff, it’s a situation that has to be faced.”

At Indiana University of Pennsylvania, the library shelves overflow with books that get little attention. A dusty monograph on “Economic Development in Victorian Scotland.” International Television Almanacs from 1978, 1985 and 1986. A book whose title, “Personal Finance,” sounds relevant until you see the publication date: 1961.

With nearly half of IUP’s collection going uncirculated for 20 years or more, university administrators decided a major housecleaning was in order. Using software from Lugg’s group, they came up with an initial list of 170,000 books to be considered for removal.

Faculty members who make their living in the stacks voiced outrage.

“Unbelievably wrongheaded” and a “knife through the heart,” Charles Cashdollar, an emeritus history professor, wrote to the president and provost. “For humanists, throwing out these books is as devastating as locking the laboratory or studio or clinic doors would be for others.”

Though “weeding” has always taken place at libraries, experts say the pace is picking up. Finances are one factor. Between staffing, utility costs and other expenses, it costs an estimated $4 to keep a book on the shelf for a year, according to one 2009 study. Space is another; libraries are simply running out of room.

And, of course, the digitization of books and other printed materials has dramatically affected the way students do research. Circulation has been going down for years.

Libraries say they needed to evolve and make better use of precious campus real estate. Students still flock to the library; they’re just using it in different ways. Bookshelves are making way for group study rooms and tutoring centers, “makerspaces” and coffee shops, as libraries seek to reinvent themselves for the digital age.

“We’re kind of like the living room of the campus,” said Oregon State University librarian Cheryl Middleton, president of the Association of College and Research Libraries. “We’re not just a warehouse.”

It’s a radical shift. Until recently, a library’s value was measured by the size and scope of its holdings. Some academics still see it that way.

At Syracuse University, hundreds of faculty and students objected to a plan to ship books to a warehouse four hours away. The school wound up building its own storage facility for 1.2 million books near campus.

At IUP, a state university 60 miles (96 kilometers) from Pittsburgh, faculty reacted with alarm after school officials announced a plan to discard up to a third of the books.

Cashdollar argued that circulation is a poor indicator of a book’s value, since books are often consulted but not checked out. Substantially thinning a library’s print collection also ignores the role of serendipity in research — looking for one book in the stacks and stumbling upon another, leading to some new insight or approach, Cashdollar and other critics say.

“We’re going to throw away as many of them as the library can get away with, which is not a strategy,” said IUP history professor Alan Baumler. “They say they want more study areas for students, but I find it hard to believe there is no place else for students to study.”

The library project is more about responsible stewardship of the state’s resources than it is an effort to free up space, Provost Timothy Moerland said. But he understands his colleagues’ passion.

“There are some who will never be comfortable with the idea of any book ever leaving this mortal coil,” he said.

Libraries say the goal is to make their own collections more relevant to students while also making sure weeded materials aren’t lost to history. A large digital repository called HathiTrust has commitments from 50 member libraries to retain more than 16 million printed volumes. Another 6 million have been preserved by the Eastern Academic Scholars’ Trust, a consortium of 60 libraries from Maine to Florida.

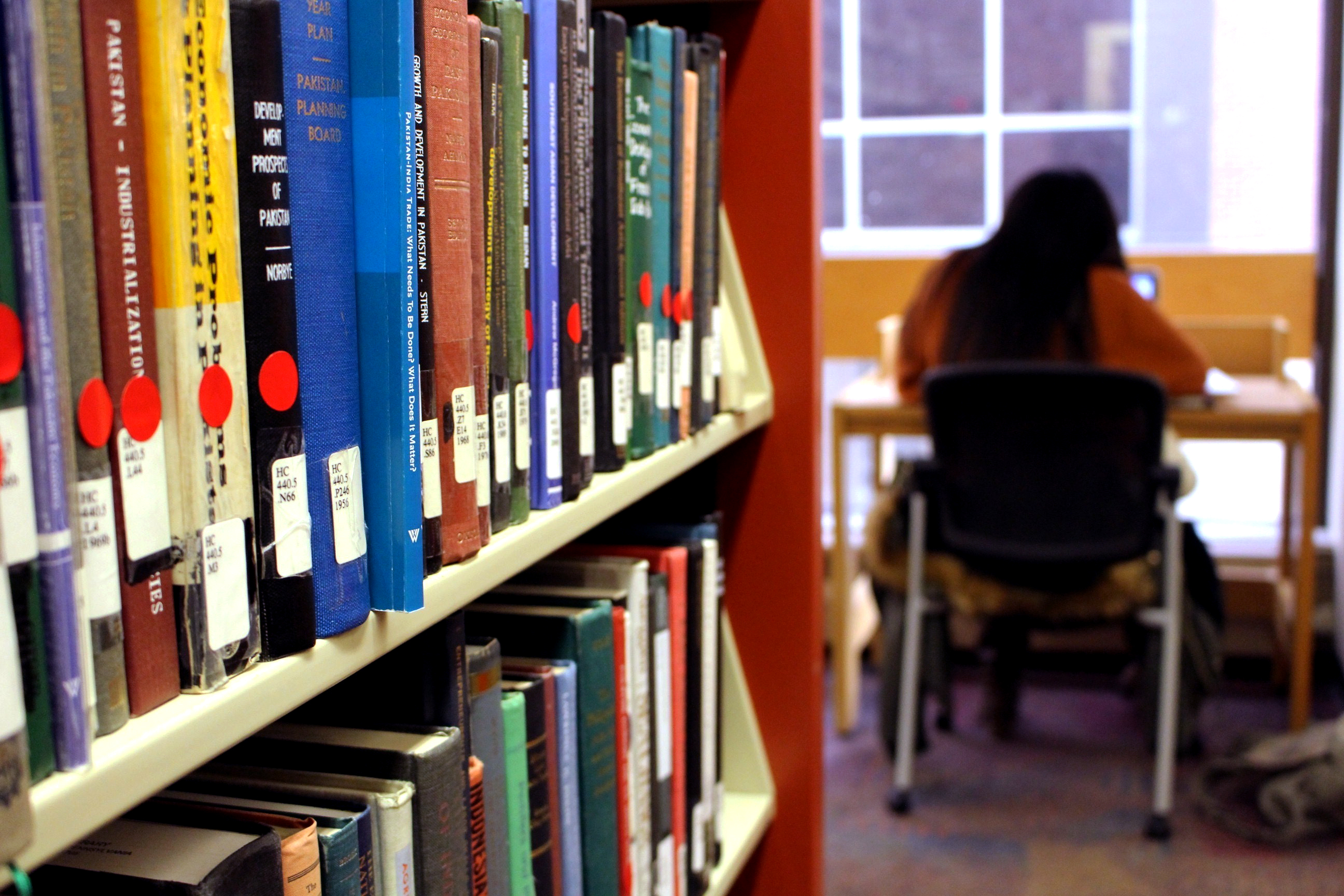

An IUP faculty committee is reviewing what Moerland dryly calls the “hit list” to make sure important works stay on the shelves. The final number of books to be removed has yet to be determined, but the potential scale is readily apparent. Librarians have affixed large red stickers to the spines of hit-listed volumes.

Some students say they worry about missing deadlines if they have to wait for a book the library no longer has. Others, like 19-year-old freshman Dierra Rowland, say they’re on board.

“If nobody’s reading them,” she said, “what’s the point of having them?”