John Baldessari, who pioneered a new genre of art in the 1970s and in the process helped elevate Los Angeles’ status in the art world from that of back-water berg to a center of the Conceptual movement, has died at age 88.

Baldessari died Thursday at his home in Los Angeles, the artist’s representatives at New York’s Marian Goodman Gallery confirmed Monday.

“It is with immense sadness that I write to let you know of the death of the intelligent, loving and incomparable John Baldessari,” Goodman said in a statement. “The loss to his family, his fellow artists, his studio staff, friends and devoted former students is beyond measure.”

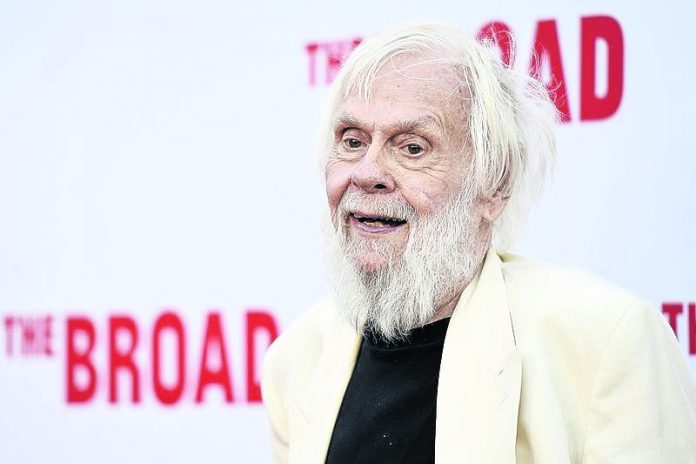

A giant in the world of art both literally and figuratively — he stood 6-feet-7-inches tall — the bearded, shaggy-haired Baldessari produced thousands of works, many of which have been exhibited all over the world and are in the collections of major museums from Los Angeles to New York.

He also influenced dozens of other artists, both with his work and as a teacher at the prestigious California Institute of the Arts and the University of California, Los Angeles.

“His legendary class in Post-Studio Art bestowed on those of us with enough brains to notice a feeling of unbelievable luck of being in exactly the right place at the right time for the new freedoms in art,” fellow artist David Salle wrote in the 2013 introduction to a lengthy interview he conducted with Baldessari, his CalArts professor in the early 1970s.

Student met teacher at a time not long after Baldessari, having grown frustrated with his own abstract expressionist paintings, loaded them into 10 boxes, took them to a San Diego funeral home and burned them.

Bored with an art movement he believed had grown old and stale, Baldessari set out to create something new, creating multimedia works that among other things merged photographs with painting, sometimes included pieces of recognizable objects or body parts but in unimaginable ways and often contained perfectly formed block letters placed as captions on the paintings.

It was a style that prompted Los Angeles Times arts critic Christopher Knight to declare Baldessari “arguably America’s most influential Conceptual artist.”

Over the course of his career, which continued into his 80s, Baldessari worked in such forms as prints, sculpture, text-based art, paintings and photographs, often mixing two or more of them together.

Some of his most well known works included “God Nose,” which depicted a nose in the sky with those two words under it; “The Intersection Series: Person and Dog/High Rise Building,” a mixture of photography and acrylic that included a dog, a building, a car and other images; and “Double Bill :… And Matisse,” which combined inkjet print on canvas with acrylic and oil paint to display a pair of walking legs and the words, “Just Matisse.”

Those works and others often struck viewers as both brilliantly constructed and at the same time whimsical, although Baldessari insisted he was never trying to be funny. Instead he compared himself to a mystery writer, providing clues to the reader, or in this case the viewer, and letting them figure it out.

”I go back and forth between wanting to be abundantly simple and maddeningly complex,” he told Salle during that 2013 interview. “I always compare what I do to the work of a mystery writer— like, you don’t want to know the end of the book right away.”

Although he may not have deliberately intended his work to be humorous, Salle told The Associated Press on Monday, humor, irony and humanity were so imbued in Baldessari’s personality that they became “almost like the delivery system of his work.”

“And then later on, at some point he added to that visual glamour, which was very much apart from other Conceptual artists who were much more restrained,” Salle added. “That was a winning combination that made his work accessible and pleasurable and complex and dense all at the same time.”

John Anthony Baldessari was born on June 17, 1931, in National City, California, a small town on both the edge of San Diego and the Mexican city of Tijuana. His father, a salvage dealer, was from Austria and his mother from Denmark.

Showing artistic talent from an early age, he was often chosen by teachers to create murals or other art projects. After high school, he decided to study art at San Diego State University despite his father’s concerns that it could be something he’d struggle at to earn a living.

After earning a master’s degree, he went on to teach art at his alma mater, at local public schools and, for one summer, at a camp for teenage juvenile delinquents. He would joke in later years that it was likely his imposing size as much as his artistic skills that earned him that latter job.

He was also painting and showing his work, although by the late 1960s he’d begun to grow bored with what he and others were producing.

Before torching his paintings in 1970, he created a magazine cover that depicted a copy of a painting with the words, “This is not to be looked at” painted underneath the work as a caption.

After incinerating his own work, he began teaching at CalArts, where his students included Salle, Mike Kelley, Barbara Bloom and other future prominent artists.

Later he taught for several years at UCLA.

Over the years, he collected numerous honors, including the National Medal of Arts from President Barack Obama.

His works are in the collections of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, New York’s Whitney Museum, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and in Los Angeles’ The Broad, the Museum of Contemporary Art and the County Museum of Art.

“He’s someone who’s had over 377 solo exhibitions, been part of more than 1,500 group exhibitions, who has produced over 4,000 works of art,” former MOCA director Philippe Vergne said when the museum honored him in 2015.

As the accolades accumulated over the years, the soft-spoken artist remained humble, even mocking his work during a 2018 appearance on “The Simpsons,” in which he discusses art with Marge.

“I still have that vestigial idea that all these other people are artists. I’m an artist wannabe,” he told Salle in 2013.

When Salle told him he’d created a movement that altered art history, he laughed.

“I thought I was going to teach high school, maybe have a family, and do art on the weekends,” he replied.

Survivors include Baldessari’s daughter, Annamarie, and son, Tony.