(Oranjestad)— This year we celebrate a few milestone anniversaries on Aruba, one of them being the 200th anniversary of when gold was first discovered on the island. We have talked about the Bushiribana Gold Mill Ruin before and its brief history during the gold industry on Aruba, but get to know a little more about the history of the “Aruban Gold Rush.”

The first hint of gold on Aruba actually dates back to 1725, when rumors about gold being found in dug up treasure chests of the Spanish colonial era prompted the first official exploration for gold on the island, commissioned by the Dutch West India Company. Under the leadership of Mr. Paulus Printz, a three-year search was conducted on Aruba, to no avail. Though they found some specks of gold, it was not enough to motivate a further search, and the assignment was discontinued by Printz himself.

It wasn’t until 100 years later, in 1824, when a young farmer boy named Willem Rasmijn found a lump of gold while out herding his father’s sheep in the area of Rooi Fluit on the north coast. His father took it to a local merchant who then sold the lump for $70. Unbeknownst to the boy and his father, they quite literally struck gold, and as word got out, a gold fever spread among the locals who started searching for more gold.

When the colonial governor in Curacao, Governor Cantz’laar, heard about the news, he sent his adjutant, Capitan van Raders, to start harvesting gold. This was in July 1824. In august of that same year, the governor followed suit to the island, accompanied by high-ranking military officials. When citizens started swarming the area in search for gold, The Netherlands sent more troops to safe guard the gold.

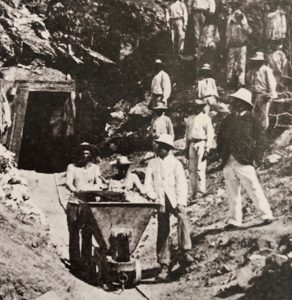

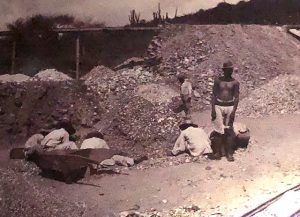

Prominent places where gold was found was in Daimari, Wacobana, Arikok, Rooi Fluit, Hadicouradi and later West punt, where gold ore was found. Because of a lack in advanced technology and materials to harvest the gold, the process took a more primitive approach: Clay rocks containing traces of gold were left to dry in the sun. Then, workers would start chipping the clay away on a large canvas to catch the gold particles that were left behind after the wind blew away the dust from the clay.

In the harvest period of 1824-1825, there was a total of 71,000 kilos collected through commissioned harvesting. Locals themselves reportedly found about 25 pounds worth of gold in the nearby rivers. The following years after that first big harvest, commission work fell off, and in 1828, the director of the goldmines, Johan Gravenhorst, decided to halt harvesting.

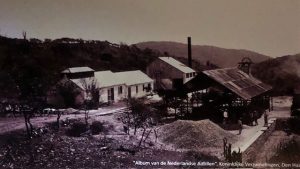

Almost 40 years later, the London-based Aruba Island Gold Mining Company Ltd. was granted concession. The firm built their gold mines on Bushiribana, and in the port of Oranjestad a long road that connected the gold mill to the port. The ores themselves came from Sero Plat en Sero Cristal.

By this point, workers were still using primitive methods to harvest the ores. For example, when someone had to go into the mines, there were no stairs or lifts; the person had to be brought down in a big bucket, with two or more workers holding the bucket by a thick rope above ground.

Aruba Island Gold Mining Company Ltd. reportedly operated until 1899, and right after the Aruba Gold Concession Ltd. was established, coincidentally also based in London. This time, the gold mill in Balashi was built, and more mines were dug up all around the island. The gold ores that were found were transported via track engine, locally called the “trekinchi”. Despite being more equipped for the job, the Aruba Gold Concession Ltd. could not produce any real profit, and so the concession was terminated just eight years later, in 1908.

A local firm, the “Aruba Goud Maatschappij” (Aruba Gold Company) took over the concession, along with all the materials and equipment. In the beginning, the company saw good profit, and for a while, the island’s economy depended primarily on the mining and harvesting of gold. But just like its predecessors, the streak of luck for the Aruba Gold Company came to an end when WWI broke out.

The main reason why production stopped this time was reportedly because of a lack in dynamite for extracting the ores from the mines, as well as a lack in raw materials like German cyanide for the refining process. By the time the war ended, the equipment that was left at Balashi were too old to use again. After the war, gold production on the Aruba was left to a standstill.

According to an issue in Aruba Esso News paper in 1953, Henny Eman wanted to start up digging again, this time using independent miners. He argued that there was proof of more gold to be discovered. Plus, hiring independent miners would boost the island’s employment rate.

When it was proven that gold was in fact still present, the executive board on the island promised to fund the project only if the gold dug up proved to be valuable. However, nothing else was reported after this, so it could be concluded that there was no real profitable market on the island anymore.

The ruins of the Bushiribana and Balashi Gold Mills are still standing, and open for the public to visit. These structures offer a glance into the past, to a time where Aruba experienced one of its first wave of industrialization. Today, these structures are persevered as historical monuments.

Source:

1. “De Kolibrie op de Rots (en meer over the geschiedenis van Aruba)” by Evert Bongers.

2. Aruba Esso News, 1953 issue.