(Oranjestad)—In celebration of the National Hymn and Flag Day on March 18th, for the next two weeks Aruba Today will be dedicating some of its pages to the history and development of the Aruban independence from the former Netherlands Antilles. For this issue, we will share a brief history of the Status Aparte (latin: separate state), which was achieved in 1986 and is considered as the Aruban Independence Day.

The call for independence from Aruba first emerged in the 1930s. At the time, the desire for more autonomy did not necessarily mean separation from the Dutch Kingdom, but rather a call to be less submissive to the central power in Curacao, through which the Dutch exercised control on the western Dutch Antilles. In the 40s, the separatist movement was led by politician J.H.A. “Henny” Eman, better known as “Shon A.”

Between September 1947 and January 1948, 2,147 Arubans signed a petition in which they asked Queen Wilhelmina to be financially, economically, administratively and governmentally separate from Curacao. On March 18th, 1948, Shon A’s son, C.A. “Albert” Eman submitted the petition during the Round Table Conference and to the Queen.

It wasn’t until the late 60s—after the passing of Albert as leader of the AVP party which strived, yet failed multiple times, to achieve true independence, did a new party leader turn the page on the fight for Status Aparte. Gilberto Francois “Betico” Croes, a former member of AVP, established his own party Movimiento Electoral Arubano (MEP) and would later become the island’s “liberator”, as he achieved what his predecessors could not.

A nationalist, Betico put the Aruban identity and folklore central in his campaign. With this, he emphasized the Latin-American and Indigenous identity on the island, as well as the Aruban “cunuceros” (farmers), contrasting this with the Afro-Caribbean character of Curacao and the old elite families on the island. For Betico’s nationalist movement, the emancipation was not only political and administrative, but also ethnic. At the time, this ideal proved to be highly successful, and MEP had already become the biggest party on Aruba by 1973.

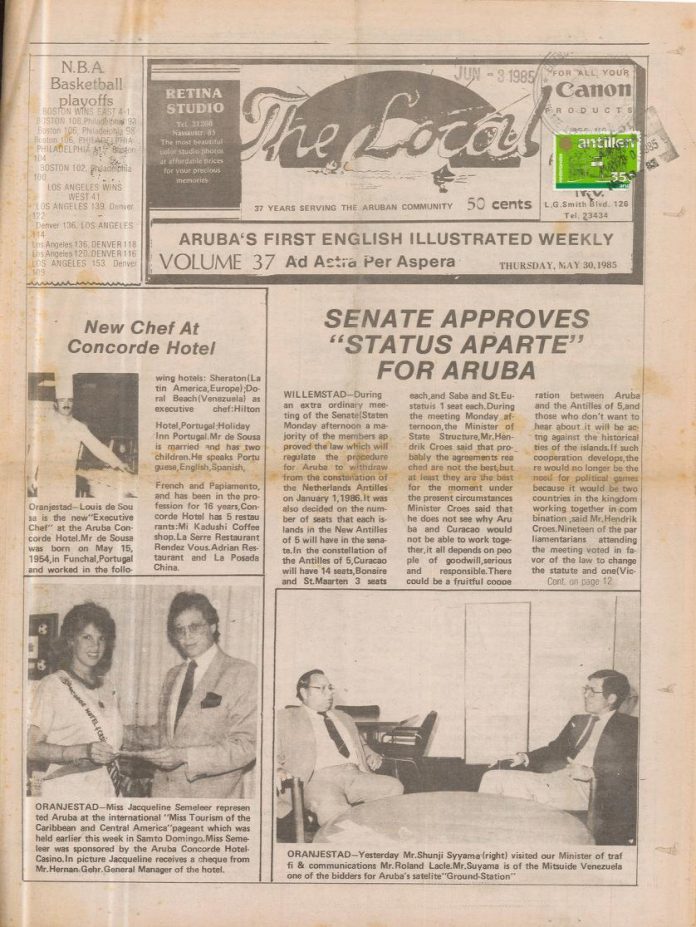

Between 1975-1985, MEP held more than half of the seats in the Island Council, and the party participated in various governments. After years of back and forth—which at one point even resulted in a deadly conflict, The Netherlands agreed in 1985 to grant Aruba its Status Aparte and for the island to be recognized as a separate country within the Dutch Kingdom, this taking effect on January 1986. However, The Netherlands had its own condition with which Aruba had to comply; independence could only be accepted on the island in 1996. For the Dutch, this was a way to prevent Curacao and Bonaire from following in the footsteps of Aruba and essentially dissolving the Netherlands Antilles. But for Betico and the Aruban community, this was the win they fought for.

The fight for Status Aparte was the beginning of the Aruban nationalism and pride. On March 18th, 1976, 30 years after Albert Eman submitted the first petition for autonomy, Aruba adopted its official flag and hymn “Aruba Dushi Tera” (Aruba Sweet Land). So even though we call March 18th our Nacional Hymn and Flag Day, what we celebrate in essence is the freedom for which our founding fathers fought tirelessly.

Source: Aruba y su status aparte : logro di pasado, reto pa futuro, 1986-2001 (Aruba and its Status Apart: achievements of the past, challenge for the future, 1986-2001).