Eleazar Hernández slept on a sidewalk amid a light drizzle, temperatures that dipped close to freezing and the roar of passing trucks.

The 23-year-old Venezuelan migrant was trying to make it to the Colombian city of Medellin with his wife, who is seven months pregnant.

But the couple had run out of money for transportation by the time they reached Pamplona, a small mountain town over 300 miles (482 km) away from their final destination. Unable to buy a bus ticket, Hernández pinned his hopes on catching a ride on the back of a truck. It was the safest way to cross the Paramo de Berlin, a freezing plateau located at 13,000 feet (4,000 meters).

“My wife can barely walk,” said Hernández, who had spent four days sleeping on Pamplona’s sidewalks. “We need transport to get us out of here.”

After months of COVID-19 lockdowns that halted one of the world’s biggest migration movements in recent years, Venezuelans are once again fleeing their nation’s economic and humanitarian crisis.

Though the number of people leaving is smaller than at the height of the Venezuelan exodus, Colombian immigration officials expect 200,000 Venezuelans to enter the country in the months ahead, enticed by the prospects of earning higher wages and sending money back to Venezuela to feed their families.

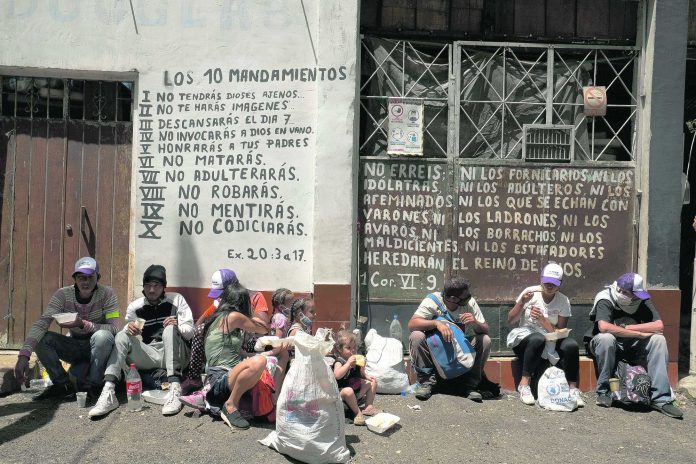

The new migrants are encountering decidedly more adverse conditions than those who fled their homeland before COVID-19. Shelters remain closed, drivers are more reluctant to pick up hitchhikers and locals who fear contagion are less likely to help out with food donations.

“We hardly got any lifts along the way,” said Anahir Montilla, a cook from the Venezuelan state of Guarico who was approaching Colombia’s capital after traveling with her family for 27 days.

Before the pandemic, over 5 million Venezuelans had left their country, according to the United Nations. The poorest left on foot, walking through a terrain that is often scorching but can also get frigidly cold.

As governments across South America shut down their economies in hopes of stopping the spread of COVID-19, many migrants found themselves without work. Over 100,000 Venezuelans returned to their country, where at least they’d have a roof over their heads.

Today, official land and bridge crossings into Colombia are still closed, compelling migrants to flee through illegal pathways along the porous 1,370-mile (2,200-kilometer) border with Venezuela. The dirt roads are controlled by violent drug trafficking groups and rebel organizations like the National Liberation Army.

“The return of Venezuelan migrants is already happening even though the border is closed,” said Ana Milena Guerrero, an official for the International Rescue Committee, a humanitarian non-profit organization helping migrants.

What’s more, many are now forced to walk within their own country for days to reach the border due to gas shortages that have diminished transportation between cities.

Hernández said it took him a week to walk from his hometown of Los Teques to Colombia.

“I can’t allow my daughter to be born in a place where she might have to go to bed hungry,” he said, while registering with a humanitarian group that handed out backpacks with food and hats for cold weather.

Once in Colombia, the migrants typically walk along highways or wait to hitch a ride. But that’s also become harder.

“It’s been very tough,” said Montilla, who was still 200 miles (321 km) away from her final destination. “But at least with a job in Colombia, we can afford new shoes and clothes. We couldn’t do that in Venezuela.”

One lengthy stretch of road connecting the border city of Cucuta to Bucaramanga further inland used to be home to 11 shelters for migrants. Most have been ordered to close by municipal governments trying to contain coronavirus infections.

Before the pandemic broke out, Douglas Cabeza had turned a shed next to his house in Pamplona into a shelter that housed up to 200 migrants a night. Now he lends gym mattresses to those sleeping outside, hoping to provide them with some protection from the cold.

“There are many needs that aren’t being met,” Cabeza said. “But with small gestures like this, we are trying to do something for them.”

Once the migrants reach their destination, a new list of worries sets in. Colombia’s unemployment rate rose from 12% in March to almost 16% in August. Those who can’t afford to pay rent are being evicted from their homes. Further complicating matters, more than half of all Venezuelans in Colombia have no legal status.

Still, for many, the prospect of earning even less than the minimum wage is a boost. Colombia’s monthly minimum wage is currently worth around $260, far higher than Venezuela’s measly $2.

Hernández was working as a street vendor in Venezuela, selling cakes baked by his wife. But money for food was becoming increasingly scarce, which prompted the couple to make the 860-mile (1,384-kilometer) journey to Medellin.

“I am Venezuelan and I love my country,” he said. “But it has become impossible to live there.”