A camera trap photo of an injured tigress and a forensic examination of its carcass revealed why the creature died: a poacher’s wire snare punctured its windpipe and sapped its strength as the wound festered for days.

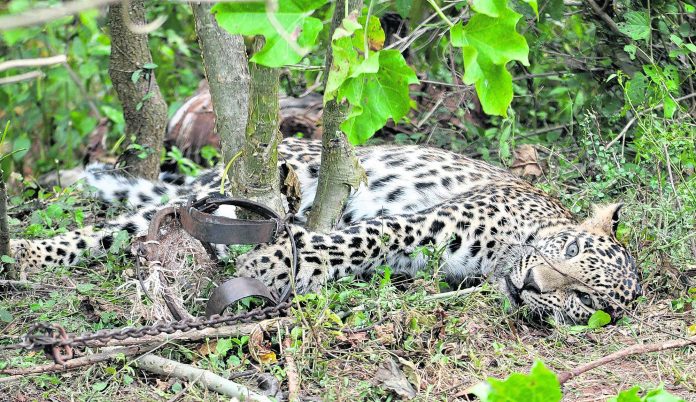

Snares like this one set in southern India’s dense forest have become increasingly common amid the coronavirus pandemic, as people left jobless turn to wildlife to make money and feed their families.

Authorities in India are concerned this spike in poaching not only could kill more endangered tigers and leopards but also species these carnivores depend upon to survive.

“It is risky to poach, but if pushed to the brink, some could think that these are risks worth taking,” said Mayukh Chatterjee, a wildlife biologist with the non-profit Wildlife Trust of India.

Since the country announced its lockdown, at least four tigers and six leopards have been killed by poachers, Wildlife Protection Society of India said. But there also were numerous other poaching casualities — gazelles in grasslands, foot-long giant squirrels in forests, wild boars and birds such as peacocks and purple morhens.

In many parts of the developing world, coronavirus lockdowns have sparked concern about increased illegal hunting that’s fueled by food shortages and a decline in law enforcement in some wildlife protection areas. At the same time, border closures and travel restrictions slowed illegal trade in certain high-value species.

One of the biggest disruptions involves the endangered pangolin. Often caught in parts of Africa and Asia, the anteater-like animals are smuggled mostly to China and Southeast Asia, where their meat is considered a delicacy and scales are used in traditional medicine.

In April, the Wildlife Justice Commission reported traders were stockpiling pangolin scales in several Southeast Asia countries awaiting an end to the pandemic.

Rhino horn is being stockpiled in Mozambique, the report said, and ivory traders in Southeast Asia are struggling to sell the stockpiles amassed since China’s 2017 ban on trade in ivory products. The pandemic compounded their plight because many Chinese customers were unable to travel to ivory markets in Cambodia, Laos and other countries.

“They are desperate to get it off their hands. Nobody wants to be stuck with that product,” said Sarah Stoner, director of intelligence for the commission.

The illegal trade in pangolins continued “unabated” within Africa but international trade has been disrupted by port closures, said Ray Jansen, chairman of the African Pangolin Working Group.

“We have witnessed some trade via air while major ship routes are still closed but we expect a flood of trade once shipping avenues reopen again,” Jansen said.

Fears that organized poaching in Africa would spike largely have not materialized — partly because ranger patrols have continued in many national parks and reserves.

Emma Stokes, director of the Central Africa Program of the Wildlife Conservation Society, said patrolling national parks in several African countries has been designated essential work.

But she has heard about increased hunting of animals outside parks. “We are expecting to see an increase in bushmeat hunting for food – duikers, antelopes and monkeys,” she said.

Jansen also said bushmeat poaching was soaring, especially in parts of southern Africa. “Rural people are struggling to feed themselves and their families,” he said.

There are also signs of increased poaching in parts of Asia.

A greater one-horned rhino was gunned down May 9 in India’s Kaziranga National Park — the first case in over a year. Three people, suspected to be a part of an international poaching ring, were arrested on June 1 with automatic rifles and ammunition, said Uttam Saikia, a wildlife warden.

As in other parts of the world, poachers in Kaziranga pay poor families paltry sums of money to help them. With families losing work from the lockdown, “they will definitely take advantage of this,” warned Saikia.

In neighboring Nepal, where the virus has ravaged important income from migrants and tourists, the first month of lockdown saw more forest-related crimes, including poaching and illegal logging, than the previous 11 months, according to a review by the government and World Wildlife Fund or WWF.

For many migrants returning to villages after losing jobs, forests were the “easiest source” of sustenance, said Shiv Raj Bhatta, director of programs at WWF Nepal.

In Southeast Asia, the Wildlife Conservation Society documented in April the poisoning in Cambodia of three critically endangered giant ibises for the wading bird’s meat. More than 100 painted stork chicks were also poached in late March in Cambodia at the largest waterbird colony in Southeast Asia.

“Suddenly rural people have little to turn to but natural resources and we’re already seeing a spike in poaching,” said Colin Poole, the group’s regional director for the Greater Mekong.

Heartened by closure of wildlife markets in China over concerns about a possible link between the trade and the coronavirus, several conservation groups are calling for governments to put measures in place to avoid future pandemics. Among them is a global ban on commercial sale of wild birds and mammals destined for the dinner table.

Others say an international treaty, known as CITES, which regulates the trade in endangered plants and animals, should be expanded to incorporate public health concerns. They point out that some commonly traded species, such as horseshoe bats, often carry viruses but are currently not subject to trade restrictions under CITES.

“That is a big gap in the framework,” said John Scanlon, former Secretary-General of CITES now with African Parks. “We may find that there may be certain animals that should be listed and not be traded or traded under strict conditions and certain markets that ought to be closed.”