It’s the day care dilemma central to rebooting American life amid the coronavirus pandemic.

With social distancing unlikely among babies and toddlers, parents of young children across the country are debating the health and safety risks inherent in child care centers, and weighing what few alternatives they have to balancing family and work.

“The virus is on my mind all the time with my kids,” said Demi Deshazior, a doctor’s assistant at a clinic in Miami, who is agonizing over whether it’s safe to put her newborn and 2-year-old son in day care. “Maybe it will work out and the kids will be healthy and safe but there is always that ‘what if?”

Many states have issued new health and safety guidelines for licensed providers meant to help minimize infection risks. There are precautions being ordered or suggested for everything from nap time (space kids further apart) and meal times (no communal food sharing), to pick-up and drop-off (curbside). Soft toys that can’t be easily cleaned are out. Plexiglass to partition play areas are in.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is also urging child care providers to have caretakers wear masks and other personal protective equipment, clean and sanitize all surfaces more vigilantly, and screen kids and teachers with temperature checks.

And though young children have largely been spared of the worst of COVID-19, a rare and serious inflammatory condition in children that’s linked to the coronavirus has reinforced the anxiety many parents have because so much is uncertain about the virus. Dr. Danette Glassy, an American Academy of Pediatrics expert who has helped set the national health and safety standards for child care and early education programs, said parents must take stock of the specific risk factors in their family, such as underlying health conditions like diabetes and exposure to high-risk grandparents, and their personal risk tolerance.

For the latter, what’s most important is for parents to be informed about how their day care will adapt to new protocols, and to understand that the relative risk for children to become sick enough to require hospitalization or die are low to negligible.

“It’s not without risks,” Glassy said of group child care. “Nothing is except inside your home, but the risk can be very low if they’re following these guidelines.”

For most people, the new coronavirus causes mild or moderate symptoms, such as fever and cough that clear up in two to three weeks. For some, especially older adults and people with existing health problems, it can cause more severe illness, including pneumonia and death. The vast majority of people recover.

Will Gee, 39, an attorney in D.C. who is currently unemployed, said he and his wife decided to send their 3-year-old daughter back to day care. The father was struggling to care for her and an older brother, and he needed time to look for a new job and trusted their child care center to be responsible with new protocols.

“I was just really holding on by fingertips and it felt — once you know there was another option out there — it didn’t feel sustainable,” Gee said.

On the first day, Gee’s daughter, Sloane, was one of the five kids who returned to Petit Scholars in D.C., a child care program that normally cares for 100 children across three campuses, according to owner Lashada Ham-Campbell.

With enrollment capacity cut in half to minimize exposure, Ham-Campbell said she’s been on a mad hunt for plexiglass to help further divide her centers’ spaces.

“We are a mandated mask-wearing city, so everywhere you go, you’re aware the virus is here,” Ham-Campbell said.

Emily Oster, a Brown University economics professor and parenting book author, said each family’s calculus will be different but that the first step to making the decision on day care is to frame their specific choices — for example: to go back or lose their job, or to go back in two weeks versus two months.

“A lot of people were stuck on ‘Should I go back?’ — which is a question that seems like a question of yes or no, but it was hard for people to conceptualize because there’s an infinite number of things to think about,” Oster said.

And for some, it’s not much of a choice, particularly among essential workers, those who aren’t able to work from home and those who can’t afford to take time off.

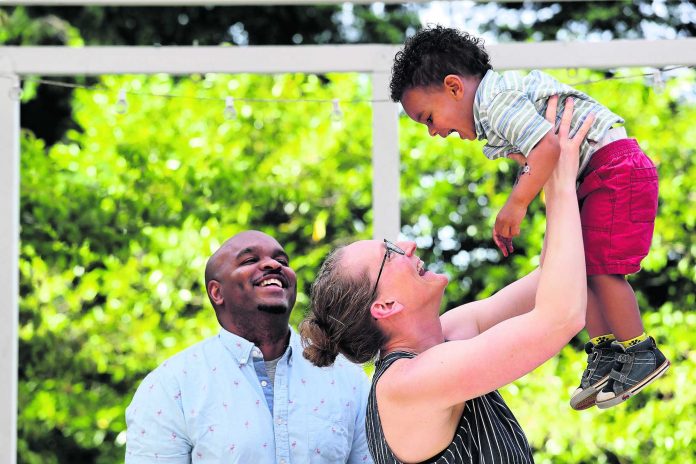

Emma Robinson, a pharmacist at a Seattle hospital, figured her child care center was no more risky than her job as an essential health care worker. The 42-year-old and her husband decided to keep their 2-year-old son, Tristan, in day care.

“I think there’s just also the fatigue of trying to do everything perfectly and worrying about everything,” Robinson said.