Havana has been ruled by Spanish colonial governors, American-backed strongmen and communist revolutionaries.

It’s an architectural jewel box where buildings collapse from lack of maintenance. It’s a coastal capital facing a sea nearly devoid of boats, thanks to U.S. sanctions and Cuban prohibitions.

Its leaders denounce global capitalism as they build new chain hotels for tourists arriving from Miami, Mexico City and Madrid.

Havana, a metropolis of conundrums and contradictions, will celebrate its 500th anniversary Saturday facing some of the toughest challenges in its history, from climate change to U.S. sanctions to the stagnation and brain drain plaguing one of the world’s last communist economies.

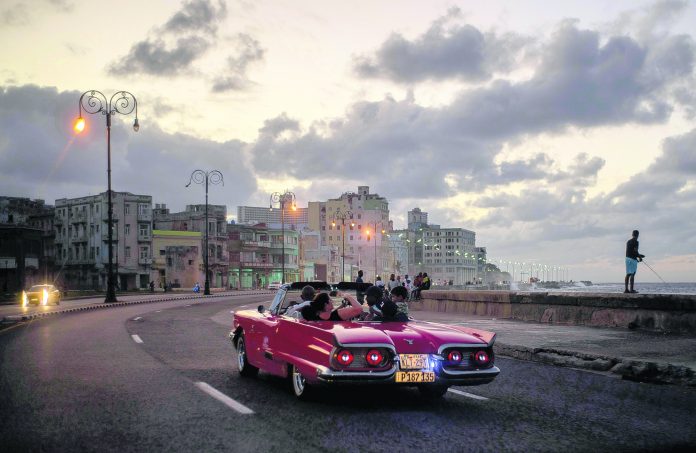

Despite the hard times, the Cuban government is planning a jubilee week, with hundreds of events at restored monuments and historic sites, a visit from the Spanish royal family and fireworks over the Malecon seaside promenade.

The mood of resignation often found on the streets of Havana has lifted slightly, with the city’s 2.1 million residents admiring the restoration work — although much appears rushed and incomplete — and enjoying street fairs and special exhibitions that have already begun ahead of the anniversary festivities.

María de los Ángeles Matamoros, a retired state worker, lives in a 19th century town house in Old Havana that has been carved up into 20 small apartments. For decades she shared a bathroom with neighbors and hauled buckets of water to her apartment from the building’s single working tap.

“I wouldn’t live anywhere else in the world. It’s a profound love,” she said. “Old Havana, where I live, it’s part of me.”

Most other Spanish capitals in Latin America retain a kernel of colonial center in a sea of glass office buildings, concrete towers and strip malls. Havana largely stopped building after its 1959 socialist revolution, and what it did put up were mostly Soviet-style apartment blocks on empty land on the city outskirts.

For tourists frustrated by the homogeneity of so many global destinations, Havana is a chance to see something unique.

“In Chile our architectural history has been lost, not conserved, something that’s really positive to see in Havana,” said Esteban Gajardo, a Chilean tourist.

A drive through the city today can take you from 16th century Spanish plazas in Old Havana to neo-Baroque apartment buildings and Art Deco theaters in central Havana to early 20th century mansions in the shady Vedado neighborhood and modernist homes in the semi-suburban districts of Miramar and Siboney.

“Havana has a very clear urban structure that grew and was maintained over time, but development practically stopped in the ’60s,” said architect Orlando Inclán, an urban development specialist at Havana’s Office of the City Historian.

Cuba allows every citizen to own two homes, one in the city and one in a rural area, and they can be freely bought and sold under laws enacted after Raul Castro became president in 2008 and launched a series of reforms.

Many buildings were saved from ruin by waves of renovation in Havana and other major cities at the hands of the country’s small upper-middle class, those with private businesses on the island or access to capital from aboard. Hundreds of thousands of other Cubans get by on the state salary of roughly $30 a month while living in homes in various states of collapse.

The degradation of homes and other buildings is being worsened by climate change, particularly in coastal areas vulnerable to flooding, sea spray and regular hurricanes and tropical storms. On the Malecon, 70% of buildings are in such poor shape that they have been slated for total or partial demolition.

Other constant complaints from Havana residents center on irregular trash pickup and piles of refuse that accumulate on street corners as well as poor public transport that transforms even short commutes into hours-long odysseys on public buses.

Car ownership is out of reach for most Havana residents so most depend on buses or antique American cars repurposed as short-haul group taxes.

“The city has a huge backlog of work to do on housing, infrastructure and services,” said Cuban architect Rolando Lloga.

Raul Castro’s reforms have largely stalled in recent years, making many Cubans pessimistic about the country’s economic future. Adding to that is U.S. President Donald Trump’s tightening of sanctions on the island, aimed in large part at cutting off tourism revenue.

Iris Flores, a secretary at a state-run business, said she is saddened by the collapse of buildings and infrastructure, anti-social behavior among young people, and unhygienic conditions and piles of trash.

Nonetheless, she said, nothing can beat crossing the Bay of Havana to the Spanish colonial Morro castle and admiring the gentle curve of the Malecon being lapped by the waves of the Florida Straits.

“I was born here,” the 57-year-old said. “And it’s in Havana where I’ll die.”q